The Embodied Perspective

Elevator Pitch

The piece Elevator Pitch has a long story. Of all the pieces that I wrote for this project, and probably in my life, this is the one that changed the most from its original idea to its final result. Initially, the piece was conceived to investigate how rhetorical figures could be translated intointo musical rules that would develop into a musical narrative.

Musical Procedural Rhetoric

Since antiquity, the study of rhetoric has been considered as a set of skills aimed at achieving a more persuasive manner of speaking and writing. The effectiveness of rhetorical communication is often achieved through linguistic devices collectively known as rhetorical figures or figures of speech. These devices rely on ornamental discursive techniques that convey meanings or functions beyond their literal interpretation. Examples include simile, metaphor, allegory, hyperbole, irony, antithesis, metonymy, synecdoche, prosopopoeia, apostrophe, climax, incrementum, and exclamation, among many others.* See for example Karl Richards Wallace, Understanding discourse; the speech act and rhetorical action (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1970).

The notion of music rhetoric has a long history in Western music, in particular in composers from the Renaissance and Baroque periods. During these periods, composers often incorporated elements of rhetoric in their works, as they viewed an intrinsic connection between the rhetoric of language and the capability of music to stir and evoke emotions in listeners through the use of affects. * Affects have been defined as emotional abstractions or idealized emotional states that a composer was expected to arouse in the listener through a musical work. Composers like Claudio Monteverdi demonstrated a profound understanding of the relationship between music and text in vocal compositions.* In 1605, Monteverdi introduced the distinction between the prima prattica and the seconda prattica, or first and second practices, something that marked a shift in composition, moving from an established style to a more modern approach. Similarly, composers of instrumental music drew inspiration from rhetorical principles to describe and refine their compositional techniques. For example, certain musical gestures, such as melodic repetition, fugal imitation, dissonance or consonance, intervallic movement patterns, and even silence, were viewed as formulas widely applicable in diverse musical contexts:

However, for this piece, the use of algorithms and computational methods to do this would move this process closer to the idea of procedure or procedural. An important concept is the idea of procedural rhetoric, developed by Ian Bogost. * Ian Bogost, Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power of Videogames (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007). This term refers to the idea that processes, especially the ones used in computing, are means of persuasion. In this light, computational algorithms represented in computer code are viewed as rhetoric agents from a perspective based on procedure as a form of facilitating action. Eventually, I ended up developing a conceptual framework for some of the constructive aspects of the piece that I termed musical procedural rhetoric, which linked the implementation of rule-based formulations using constraint algorithms for the composition of music as instances of procedural expression.* A lengthier discussion around the idea of musical procedural rhetoric can be found in my article: Juan Sebastian Vassallo, "Exploring Musical Procedural Rhetoric: Computational Influence on Compositional Frameworks and Methods in the piece 'Elevator Pitch'", International Journal of Music Science, Technology and Art 6, no. 2 (2024), https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.48293/IJMSTA-114, https://www.ijmsta.com/archive_card.php?id=114.

I wanted to link this constructive idea to a type of contemporary political communication, and how certain politicians make use of a kind of an “artificial” rhetoric to generate highly emotional and performative speeches that have the effect of driving opinion and, ultimately, manipulating thought. I became inspired by an idea discussed by philosopher Hartmut Rosa, who characterizes modern society as an accelerated society. * Hartmut Rosa, Social Acceleration: A New Theory of Modernity (Columbia University Press, 2013). https://doi.org/10.7312/rosa14834. He proposes that the latest groundbreaking technological advancements have resulted in an accelerated pace of life, ultimately leading to the experience of a chronic shortage of time. In such an environment, communications are consumed instantaneously through smartphones and social media, promoting a paradigm where communicational brevity and succinctness are essential.

This has given rise to discursive techniques like the elevator pitch, a brief speech designed to quickly convince listeners of a value proposition for a product, idea, or project. These new strategies have migrated into political communication, where they are used to craft messages that manipulate public opinion by providing selective information on pressing social issues like immigration and minority rights, often linked to authoritarian, autocratic, and intolerant political movements. The piece, thus, aims to be a sardonic analogy to a political speech, which is portrayed here as empty of substance and as an artificial construct of a computational “laboratory-made” rhetoric, relying purely on historical conventional rhetorical strategies.

How is this connected to embodiment? Well, that is to be seen –or heard? For now, I must shift focus, as it is essential to first address the constructive aspects central to this piece. I will return to the topic of embodiment later and assure the reader that these concepts will be interconnected in due course.

At the beginning of the ideation of the piece, I had in mind to investigate three main inquiries. Firstly, as the piece is inspired by this so-called type of computational “laboratory-made” rhetoric, I imagined a musical narrative that would use speech or spoken sound material as departure points for deriving musical material and operating compositional processes related to rhetoric figures. This is by no means a new or novel thing to do. * A well-known contemporary composer who has explored this approach is Jonathan Harvey. More recently, Fabio Cifariello Ciardi has developed a system to translate speech prosody as musical material. I will discuss some of their works in the section ‘Symbolic Sonification.’ However, I sought to investigate a way of doing this so that the music would relate strongly to the backdrop of the piece: the musical speech needed to evoke a political narrative, somehow giving the impression that the cello itself had become a political figure.

Secondly, looking into the possibilities of using constraint algorithms to govern the organization of idiomatic techniques and sound production types for the violoncello. A strong motivation for this was to explore ways of involving qualitative or weak * The concept of weak musical parameters is not universally accepted. However, the parameters often considered most potent are pitch, rhythm, and dynamics, with articulation sometimes viewed as a more subtle or nuanced aspect of music expression. Initially, the dominance of pitch and rhythm as the primary musical compositional domains throughout the history of Western music was addressed critically by James Tenney in the early 1960s, as he proposed that every musical parameter could hold structural importance within a musical phrase. See James Tenney, "Meta (+) Hodos: A Phenomenology of Twentieth Century Musical Materials and an Approach to the Study of Form" (Frog Peak Music, 1968). However, in computer-assisted composition, I believe that the issue of hierarchical formalizations persists, and I believe that further compositional research toward formalizations of diverse musical parameters is desired. musical parameters at an important compositional level, possibly not any less than pitch and rhythm.

Finally, I wanted to create some nonsensical text that would follow –somehow– the same constraint rules used for the musical organization. This text would be part of the piece, either as vocalized by the performer or as synthetic speech in the electronic part. In the end, I leaned on this latter approach, which I will discuss in detail later.

Musical Material and Form

The musical material is mainly derived from the musical translation of a speech fragment from Donald Trump. I analyzed the opening phrase of Trump’s inaugural speech as president of the United States* The video of it can be seen here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XZn8tFbISpo (originally retrieved on January 30, 2023). using Spear. * https://www.klingbeil.com/spear/ I focused on the melodic contour of the phrase “The time for empty talk is over,” which I translated into musical representation.

Formally, the piece is constructed as a linear flow of musical phrases that develop according to a –rather metaphoric– implementation of rhetoric figures, as they were described by the classic Quadripartite Ratio. * The Quadripartite Ratio is a rhetorical framework that dates back to classical rhetoric in Ancient Greece, often associated with Hermogenes of Tarsus. In it, the different types of rhetorical actions are described and categorized into four basic operations: adiectio, detractio, immutatio, and transmutatio. Adiectio refers to the addition of information to strengthen a particular point, often by organizing words or clauses to build intensity. Detractio involves omitting details to highlight other elements of the argument. Immutatio rearranges the order of words or phrases, and transmutatio changes the structure or form of words while keeping their meaning the same. In connection to the rhetoric idea, I chose an archetypical musical form for this piece, related to the Aristotelian concept of narrative. * Some authors have discussed the persuasive power of the Aristotelian narrative and how it has been applied to various forms of communication, from fiction to product pitches. See for example Odile Sullivan-Tarazi, "Narrative insights: notes from Aristotle on storytelling," @Medium, 2018-05-04, 2018, https://medium.com/@odile_sullivan/narrative-insights-what-aristotle-can-teach-us-about-storytelling-239d1b878e74. Ultimately, in this type of narrative structure, there is a logical chain of cause and effect where earlier events are related to current events and will be perceived as connected to future developments. Of course, I aimed to represent that musically in the way of developing the material throughout the piece.

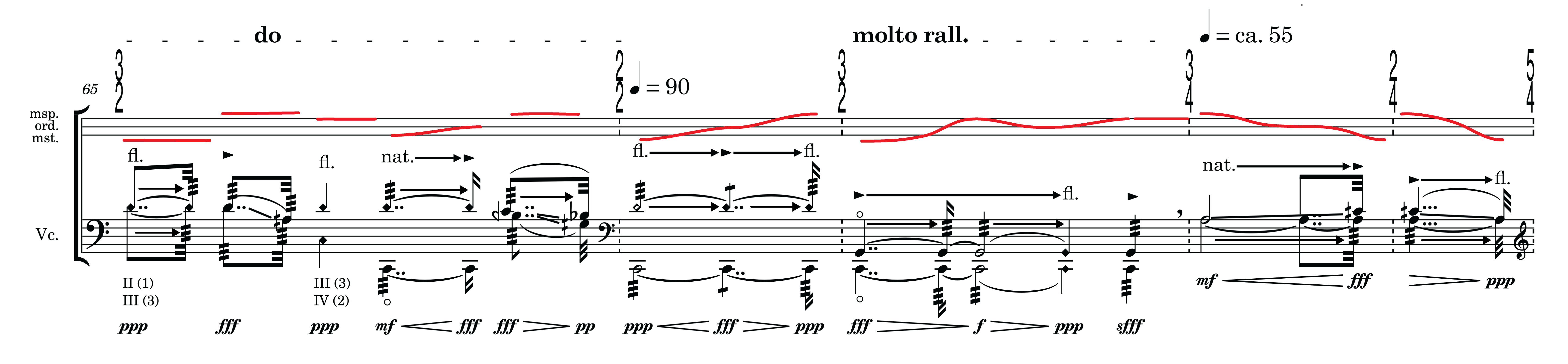

The piece begins with breath sounds presented in the electronics, a sound that proposes a type of inward-outward gesture and an interruption of the flow towards the end (halted inhaling, silence, and irregular exhaling). This gesture is important and will keep developing throughout the piece as the seed for processes of expansion, compression, and interruptions of the flow. For example, the inward-outward gesture becomes the seed for the posterior process of expansion of melodic profiles, metaphorically related to the equivalent rhetoric processes of adiectio (or auxesis) from the Quadripartite Ratio:

The gesture of interruption becomes evident within the narrative as certain musical flows are abruptly cut and juxtaposed with contrastive elements. It is possible to see, especially from m. 96, when the appoggiaturas start breaking the flow in increasingly shorter periods, and in the final section.

After the highest energetic point of the piece in m. 125, the final section takes on a bluesy tone. The narrative flow is disrupted by an overpressed C2 plus silence, leading to a breakdown of continuity by the end of the piece. Intertwined throughout these phrases is a sonic gesture created by rubbing the back of the cello’s fingerboard with a superball, producing a vocal-like sound that corresponds with the nonsensical speech elements in the electronics (the electronic component will be discussed in greater detail later).

Throughout the piece, the rhetorical categories of immutatio and transmutatio translate into structural aspects related to the unfolding of different types of instrumental techniques and idiomatic sound production types for the violoncello, such as pitch bending, tremolo, and vertical bowing tremolo. For this, I used two Lisp rules that metaphorically align with the figures of immutatio and transmutatio, expressed as two logical statements in the LISP code that are enforced by the constraint engine. The first rule involves the repetition of elements within a list (at the level of gestures, or words), while the second enforces repetition across consecutive pairs of lists (phrases). * These rules exist originally in the CAC library JBSconstraints, developed by the composer J. B. Schillingi. For some time, I studied B. Schillingi’s rules as well as other rules by Ö. Sandred and J. Vincenot as a method to learn the syntax programming language Lisp, which was not familiar to me before. Ultimately, I ended up writing my own versions of these rules as a learning process.

; rule (a)

(lambda (a b c d)

(= 3

(length

(remove-duplicates (list a b c d))))

; Example of the outcome of rule (a) using numbers:

; ( 1 1 2 3 ) ( 1 2 4 2 ) ( 4 2 4 3 ) ( 2 3 2 1 ) ( 3 3 1 4 ) ( 4 1 2 4 ) etc…

; rule (b)

(lambda (a b c d e f g h)

(progn

(setq sublist1 (list a b c d))

(setq sublist2 (list e f g h))

(= 2

(let ((counter 0))

(dolist (element sublist2)

(if (member element sublist1)

(incf counter)))

counter))))

; Example of the outcome of rule (b) using numbers:

; ( 1 2 3 4 ) ( 1 5 7 2 ) ( 2 4 5 3 ) ( 3 2 1 7 ) ( 2 4 5 7 ) etc…

Notice how rule (a) observes that in each list, only two elements repeat, and the rest are different. In the second rule (b), only two elements are repeated across consecutive lists, and within each list, the rest of the elements are different. As an example, consider the bowing position. Here the candidates have been restricted to ordinario (‘ord.’), sul ponticello (‘sul pont.’), sul tasto (‘sul tasto’), and the possible trajectories between them. The rule, thus, enforces that two bowing positions should be repeated every consecutive four.

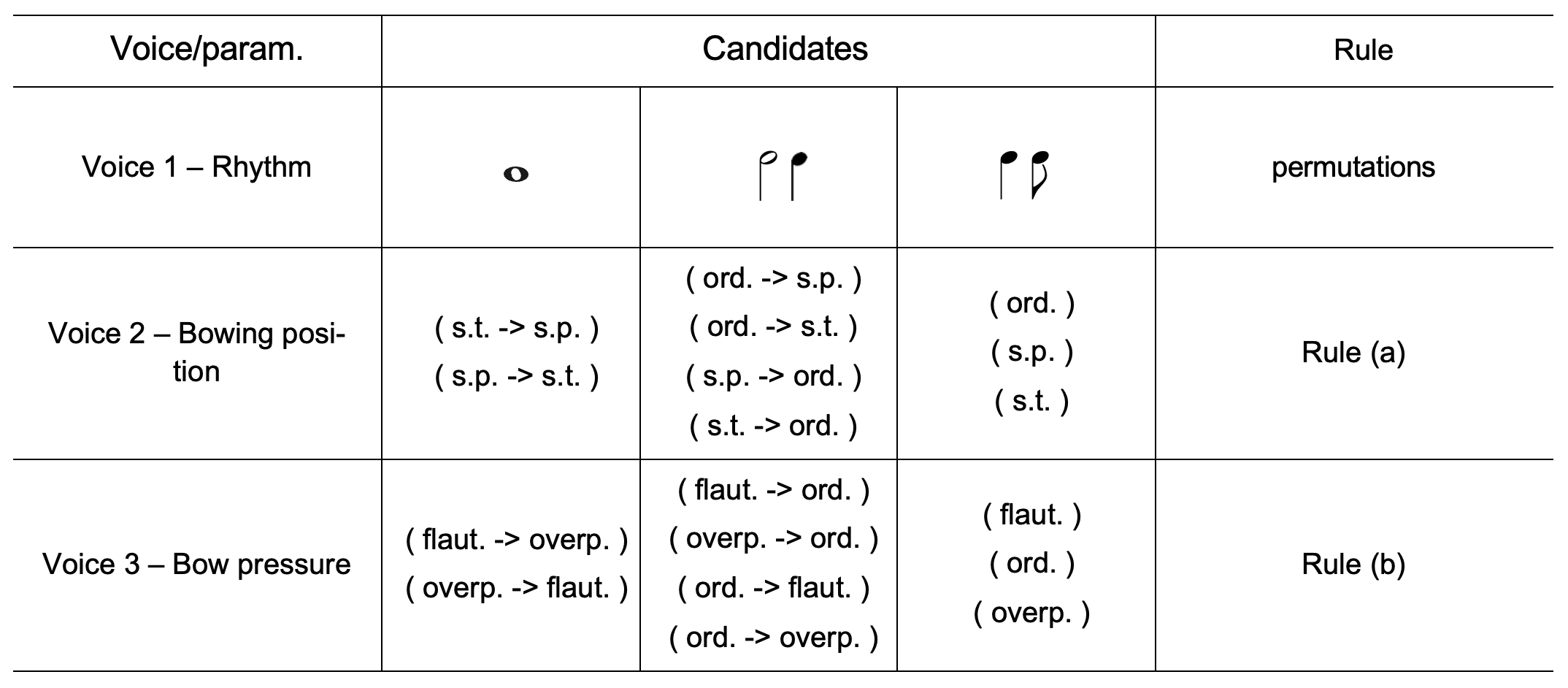

This seems to be an easily doable task “by hand,” so the question might be, why do I write code rules to do this? There’s a good answer to that. As more musical parameters become constrained simultaneously, the combinatorial possibilities increase enormously and it soon becomes a task only doable with the assistance of a computer. The table below schematically shows how the constraint engine generates a musical sequence by constraining three musical dimensions: rhythm, bowing position, and bowing pressure.

Here, the three parameters are constrained in a cascade fashion: the first dimension –rhythm– follows a permutational rule, and the candidates for the rest of the voices are constrained to certain rhythmic figures. For example, longer bowing trajectories (for example, sul pont. to sul tasto) can only occur in whole- and half-notes. Static bowing trajectories (for example, sul pont., ord., sul tasto) are restricted to quarter- and eight-notes, and intermediate trajectories occur only in half- and quarter notes. In addition, the unfolding of bowing positions and bow pressure is constrained by the rules (a) and (b) discussed above. The result is a complex, multilayered construct where independent parameters are organized through simultaneous constraint rules that establish relationships among them:

Electronics

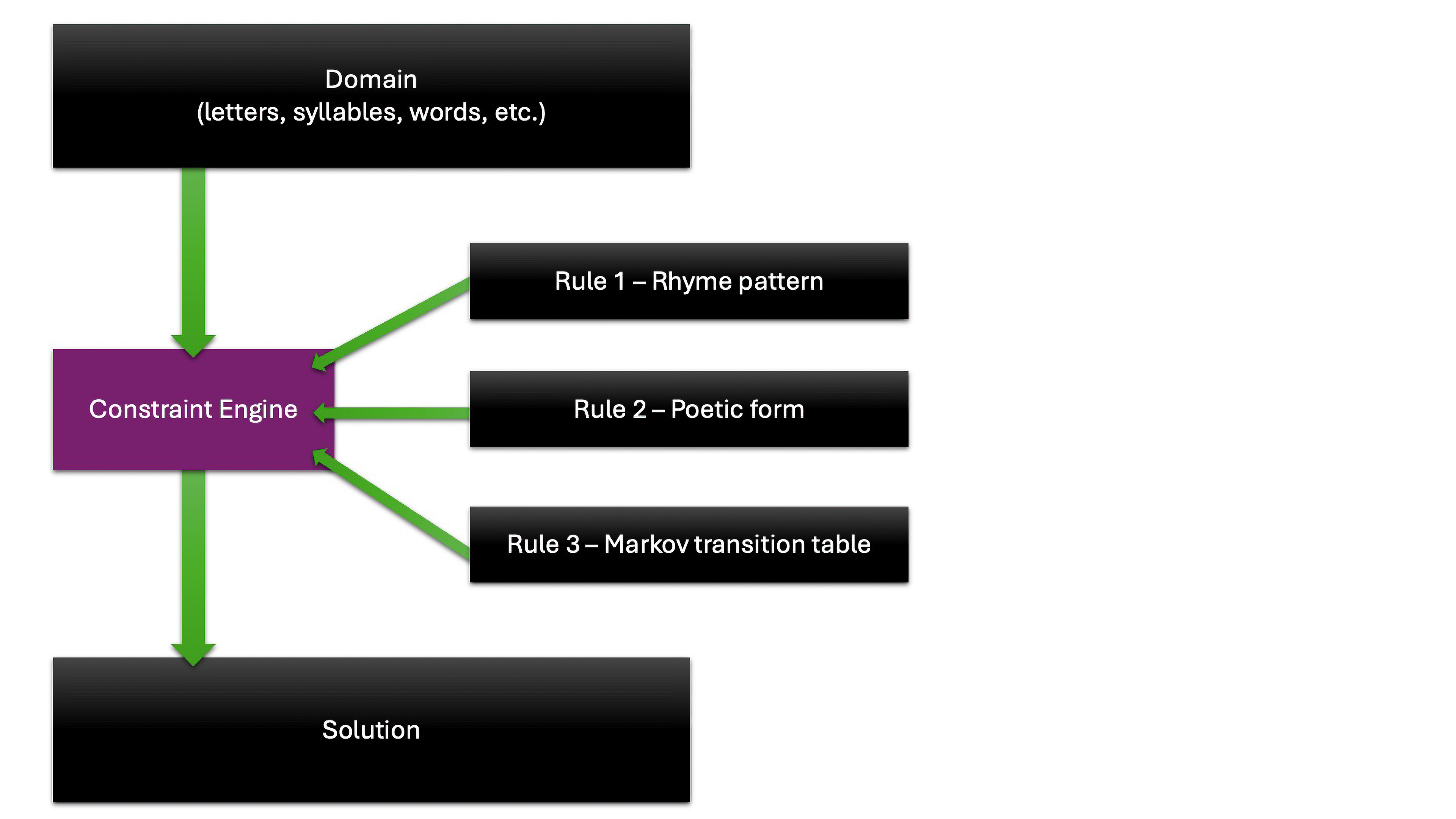

Now, I will move to the electronic part of the piece, which is where the nonsensical speech comes in. Since I had already been experimenting with the rule-based text generation for the piece Versificator – Render 3, I thought I could somehow expand on this methodology. Ultimately, the problem –or the reality– that I faced in Versificator – Render 3 was related essentially to the hyper complexity of human language and the impossibility of modeling it based on a few constraint rules. Of course, it was never my idea to do this. Rather, I used the constraint rules as a metaphor and a tool for automated generation, but clearly, the resulting text was quite simple.

From that point on, I wondered how to move into a deeper level of complexity around linguistic generative tools, * Please consider that these inquiries are pre-ChatGPT. I started working on this piece around 2021, and the idea for the second version came around mid-2022. but over which I should have some control. Then, suddenly, it hit me: Markov Chains! I knew about Markov Chains from before in my life. However, I never experimented with them until 2021 for my piece Isovell Che Segila Chentellare for eight voices. The process of composition of Isovell was rather fast and unsatisfactory. However, it was a good starting point to investigate the Markovian generation of text in my next pieces, in particular for Elevator Pitch and also for Oscillations (i).

Markov Chains

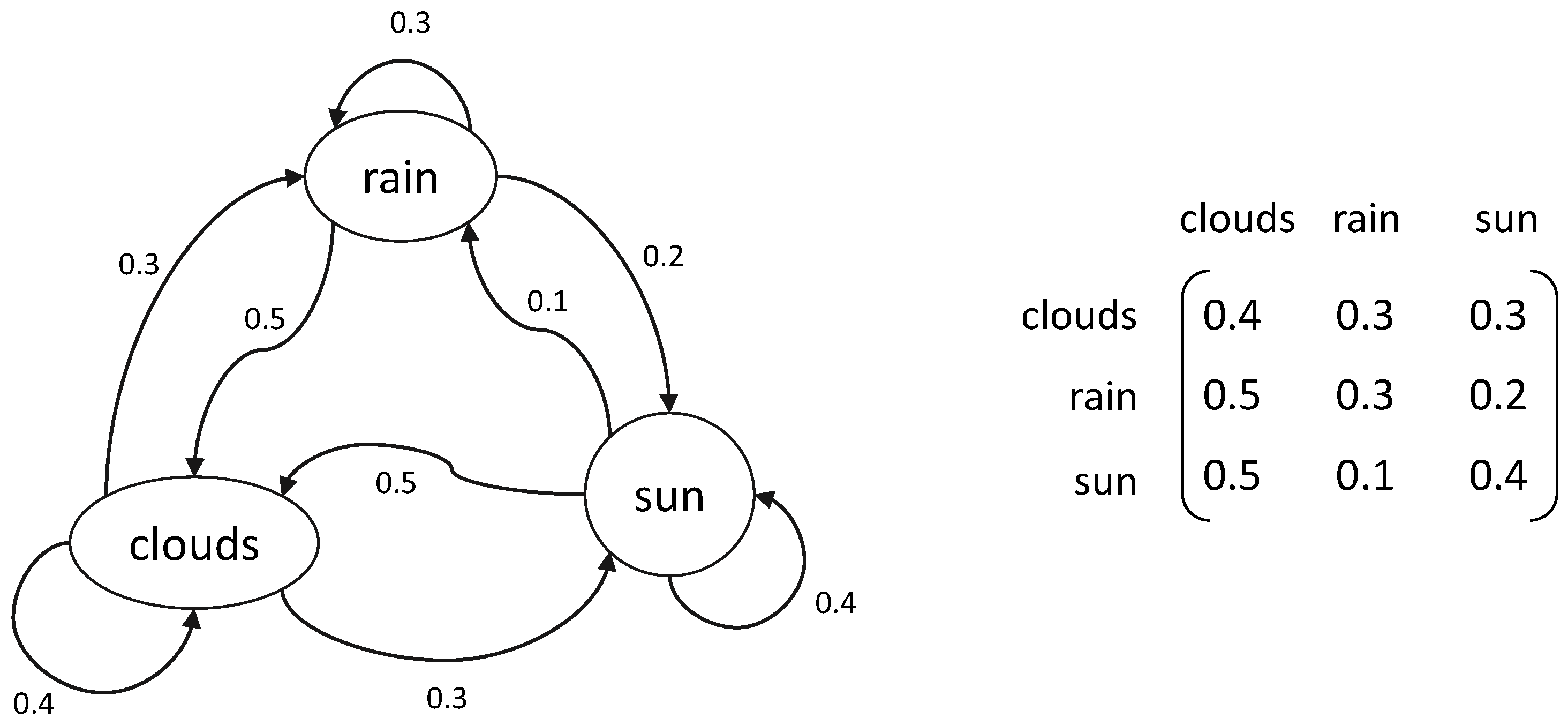

Markov Chains (MCs) were first theorized by the Russian mathematician Andrei Markov in 1906. A MC is a probabilistic model describing a sequence of possible events in which the probability of each event depends only on the state attained in the previous event. MCs are based on the analysis of consecutive events or states. In other words, a Markov model learns from some data by looking at how likely it is for an event to come after some other –or how likely it is for an event to come after two others, or three, and so on. For this reason, MCs have been used extensively to observe linguistic regularities and patterns. In fact, Markov initially used this method to observe tendencies of spelling in the written Russian language, using the text Eugene Onegin by Alexander Pushkin as a model. * Gely P. Basharin, Amy N. Langville, and Valeriy A. Naumov, "The life and work of A. Markov," Linear algebra and its applications 386 (2004), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.laa.2003.12.041. The number of consecutive states analyzed for a Markov model is known as its order.

In music, the use of MCs has mainly served two purposes. On the one hand, analytic, as MCs can provide a descriptive analysis of the probabilities of a set of musical elements occurring in a sequence. Thus, they have served as a tool for musical analysis of regularities in style, for example. On the other hand, generative, as they facilitate a simple computational generative process following the probabilities learned from a model. As the probability distribution of events of the new data follows that of the original, it will have some resemblance with it. MCs have been used, for example, for generating jazz improvisations,* Cheng I. Wang, Jennifer Hsu, and Shlomo Dubnov, "Machine improvisation with Variable Markov Oracle: Toward guided and structured improvisation," Computers in Entertainment 14, no. 3 (2016), https://doi.org/10.1145/2905371. identification and recreation of the musical style of a composer,* Maximos A. Kaliakatsos-Papakostas, Michael G. Epitropakis, and Michael N. Vrahatis, "Weighted Markov Chain Model for Musical Composer Identification" in Applications of Evolutionary Computation (Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2011); Adilson Neto and Rodrigo Pereira, "Methods on Composer Identification Using Markov Chains," (paper presented at the 16th Brazilian Symposium on Computer Music, 2017). or procedural algorithmic generation of functional or emotion-oriented music. * Adhika Sigit Ramanto and Nur Ulfa Maulidevi, "Markov chain based procedural music generator with user chosen mood compatibility," International Journal of Asia Digital Art and Design Association 21, no. 1 (2017).

In WACM, MCs also have a long history, but their creative use has been relatively superficial. Same as constraint algorithms, they were a method used for the composition of the Illiac Suite. * Hiller and Isaacson, Experimental Music: Composition with an Electronic Computer. After Lejaren Hiller, other relevant avant-garde composers used MC, such as I. Xenakis and G. Koening.* An early survey of pieces using MCs as a compositional method was written by Charles Ames in 1989. See Charles Ames, "The Markov Process as a Compositional Model: A Survey and Tutorial," Leonardo 22, no. 2 (1989), https://doi.org/10.2307/1575226. A more recent –and perhaps better-known– composer that has included MCs as a compositional method in their works is Brian Eno.*For a deeper review on Brian Eno’s methods see Rita Gradim and Pedro Duarte Pestana, "Overview of Generative Processes in the work of Brian Eno," UbiMus 2021.

At some point around the late 1980s and early 1990s, MCs became old-fashioned and ceased to interest composers. Since then, and from what I could investigate, there have been very few approaches to using MCs as a serious compositional tool. However, two of them greatly interested me and moved me to dive further into this method: the investigations carried out by Ö. Sandred*Örjan Sandred, Mikael Laurson, and Mika Kuuskankare, "Revisiting the Illiac Suite—a rule-based approach to stochastic processes", Sonic Ideas/Ideas Sonicas, no. April 2016 (2009), http://www.sandred.com/texts/Revisiting_the_Illiac_Suite.pdf. and F. Pachet.* François Pachet and Pierre Roy, "Markov constraints: steerable generation of Markov sequences", Constraints 16, no. 2 (2011), https://doi.org/10.1007/s10601-010-9101-4.

After finding out about these attempts to create steerable Markovian models, namely, Markov generators that can be compositionally controlled to a certain extent, I decided to pursue this method for a more serious artistic purpose. I began to investigate the implementation of a steered Markovian generation process facilitated by the combination of constraint algorithms and MCs by using a Markov model as a constraint rule. This method thus would facilitate the creation of the –long-advertised– nonsensical text in the piece Elevator Pitch, and experimenting with different ways of steering it became a strong motivation.

Steered Markovian Generation

The electronics in Elevator Pitch consist mainly of steered Markovian text. The source for the Markov model for the text is the same speech by Donald Trump from where I got the source for the sonification that originates the musical material. To generate this text, I combined constraint algorithms with a MC. In practice, the constraint algorithm uses a Markovian transition table as a constraint rule. This means that the constraint engine checks that every combination of candidates –the candidates are letters or syllables, depending on the order of the MC– is represented as a transition state in the Markov matrix. For this, I developed a Max abstraction that I termed MarkovConstraints, which I will discuss later in the chapter ‘Conclusions?,’ in the section ‘Contributions.’

As constraint rules are feasible to be chained, Markov rules can be combined with other constraint rules, for example, patterns of rhyme and alliteration*It is important to mention that equal typographical beginnings or endings don’t imply alliteration or rhyming—and vice versa—in the English language. This issue has been addressed in a different piece, in which this same process was done using the IPA alphabet. In that case, the correspondence between symbols and sounds is univocal. In any case, the result using the Latin alphabet was not so far from what I expected. –as I used in the piece Versificator – Render 3, or poetic structures (number of syllables and verses). As a result of this, the nonsensical text in Elevator Pitch is far more complex –and sometimes more realistic– than the one generated using solely conventional constraint rules in Versificator – Render 3.

The example below was created using a 1st-order MC in combination with a constraint rule that enforces that, for every four letters, two should be repeated and two different. The resulting text follows a 1st-order Markov probability matrix of Trump’s speech but at the same time follows the aforementioned rule:

PeoeceacayaianinviveEbyeysesrerbrcrdrudu

Mphpapipepreroeonenb

Eiuinifieferecrcarak

In the following example, I created five shorter words using the same rules discussed above, but I added a rule that constrains the text output to have a determined ending rhyme pattern (abab). The time that took the algorithm to find solutions became considerably longer:

Daldlydyoy (a)Gefeoenean (b)

Puspsosyoy (a)

Olsosasnan (b)

To take these ideas further, I expanded the Markov transition table into 2nd and 3rd order, and I started creating sentences with rhyme schemes such as ababab, as verses from a poem:

Wards overnmen itselves cities (a)Jobs families alle ones an car (b)

Kingth strulers ourse of dones (a)

Ves of mich unrealittle restar (b)

Lves rebuild first anot to res (a)

Fusing fourished intone an car. (b)

Finally, I implemented combinations of rules in order to create a sonnet with a rhyme scheme abab cdcd efef gg:

Rusten again trulerse ten your in ther,Rospense future truly mich thangs the an,

Ges contry andscattening its which pover,

Ysted it behindustem flourseasonable jan.

Magnificential mentermies that that nowled,

Repain is neight hearterseasonal trates,

Everts to everts we trationable for sted,

Deprived herent is americh with no longes.

Ge at it bush poverts deple by on today,

Lef buted ind little defend of dolle thou,

Dle face ten to be forgotte rememble decay,

Tries has willions armies that to cou.

Job dolledge alle has neign inner shards,

His movery at it back togethen too mands.

After generating the text, I transformed it into synthetic speech using AI-based voices that sound like Donald Trump (at a later stage I also added the voice of Joe Biden in the final section of the piece). Just to make it very clear, All the speech material existing in the piece has been artificially generated using an AI voice model: I used the app VoxBox by Myifone. * VoxBox by Myifone allows the user to generate speech using AI-based voices trained with voices of celebrities. It can be downloaded here: https://filme.imyfone.com/voice-recorder/. No real speech has been used.

Essentially, the idea for this electronic speech material was to appear at certain points as a type of narrated nonsensical speech conceptually connected with the idea of rhetorical formulas that drive the musical narrative, which is essentially the same for both, as it can be seen from the explanation above. This speech would also serve as material for further electronic processes, like delays, granulation, time stretching, and so on, that would enrich the texture. However, after some more experimentation with it, the spoken part became a type of alter ego of the cello part. And for this, experimenting with AI glitches became the creative focus.

AI-voice glitches

The app VoxBox –and most AI voice generators– work as TTS (text-to-speech) systems: they synthesize speech from a text input. Usually, these models generate speech that is very realistic and in a relatively high audio quality. While creating the synthetic speech from the Markovian text, I started to observe some curious behaviors of these models when they received nonsensical text. Of course, these voices are trained with hours of real speech, which is tokenized as text that matches the input with the resulting generated voice. But what happens when this text input partially aligns with the training data, or sometimes it just doesn’t? Well, glitches.

It is not so obvious to observe these glitches in the higher order Markovian text, but as soon as one starts inputting impossible combinations of letters, such as those 1st order Markov examples, these glitches appear very evidently. Some of them were so distinctive and funny that I almost re-composed the whole electronic part just to make room for these. Ultimately, I believe they became strong protagonists, and potentially, the whole thing about steering the Markov generation became a bit overshadowed by these glitches.

Strategies of de-formalization

Even though the essence of the piece is connected to rhetoric and persuasive speaking as a politically dubious skill, in it, investigated some rather formalistic approaches to organize the musical narrative. Initially, I was optimistic about the idea of rhetoric and musical procedural rhetoric as a form of musical organization and how this could bring new insights to investigate ways of organizing the material. However, in the middle of the compositional process, I almost concluded that this idea was not so great.

Shortly after a cellist tested the earlier versions of the piece, it became evident that all these procedural formulations would not work musically or expressively without further refinement. The primary issue was that the procedurally created narrative was entirely divorced from the realities of its production process. This disconnect led to significant challenges, the most salient being that the piece was extremely difficult to play. Some gestures required excessive preparation or time to establish the sound, some others were rather impractical, and certain gestures often produced unintended residual noises that overshadowed their desired sonic effect. Even though the cellist was exceptional, most of the time, these difficulties and their resolution went frankly against the conceptual idea of the piece.

After revisiting my initial compositional premises, my strategy was to de-formalize the piece, allowing it to evolve into a more organic musical work. By this, I mean a musical narrative that feels less like a battle between the performer and the instrument and more like a harmonious communion of the two. I believed that addressing these challenges would enable the piece to better embody its conceptual idea and envisioned narrative.

Anyway, to address these problems, I took up the cello and started playing the piece myself. I am not a trained cellist, and of course, some sections of the piece required highly developed technical skills. However, those presented fewer compositional problems. In essence, my strategy was to test these playing techniques, whether it was possible to smoothly transit between them, whether these transitions would have some noticeable effect on the sound, and whether this could be done at a relatively steady pace. This became a rather physical approach, strongly connected to the production process of the cello and my physical capacities. In addition, and importantly, I tried to maintain a strong “predictive” approach in terms of how these embodied experiences would extrapolate to other performers.

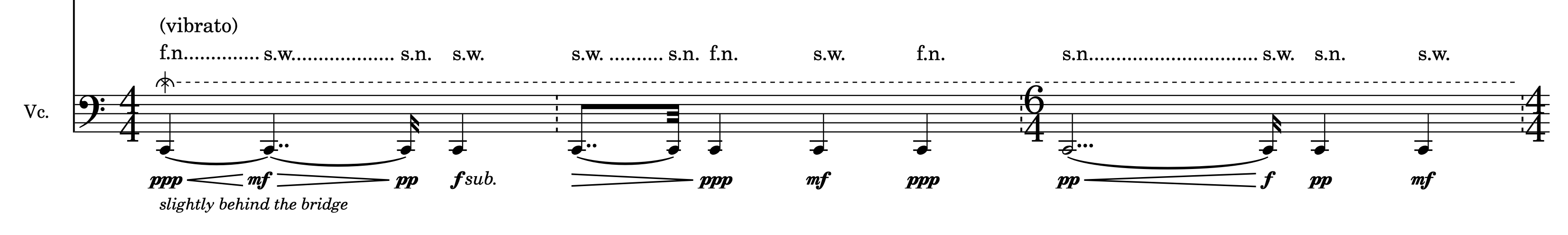

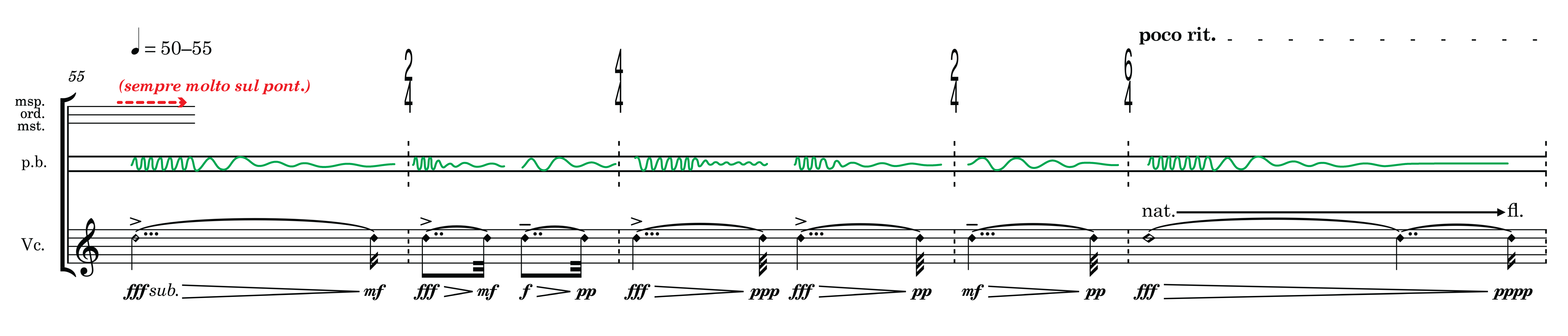

The result of this new approach based on my own experience of playing the piece –and the cello– was, most of the time, playing against my initial formalizations. Therefore, some sections were removed, and some others changed almost completely. Some structures were broken, some gestures were shaped, and ultimately, some overall flexibility was allowed. The fragment below exemplifies this. Here, the different gestures for pitch bending are the result of a constraint rule, that simultaneously deals with two parameters: pressure on the string (low, high, and low to high or high to low) and tremolo speed (fast, slow, slow to fast, or fast to slow). Below can be seen how it was conceived initially conceived and notated. The staff below shows the last version of the same passage, where the symbols were replaced by handmade lines. In addition to these de-formalization strategies, the refinement of the notation played a crucial role, especially by the introduction of graphic elements –such as hand-made color lines and SVGs* SVG (Scalable Vector Graphics) format is an XML-based vector image format for two-dimensional graphics. – in tandem with Dorico*https://www.steinberg.net/dorico/ and Adobe Illustrator. *https://www.adobe.com/

It can be argued that the underlying compositional structure still stems from constrained and procedural logic, which is ultimately a formal system, clearly expressed through the Lisp rules. The musical sound and gestures, and ultimately the way of notating them, reflect their –embodied?– production process. The nature of the constraint rules, when possible, adapts to the organicity needed to develop a narrative that reflects a broader poetic idea.