Conclusions?

Throughout this reflection, I have discussed the conceptual background and constructive processes underlying the works that constitute the artistic outcome of the project. These discussions were framed within paradigms and theories from cognitive science, drawing connections between human cognition and computational frameworks from the field of AI. This parallel essentially was aimed at better understanding aspects of creative cognition based on how computers attempt to simulate it. Additionally, discussion around these methodologies sought to illustrate some constructive aspects of the works.

A reader might claim, however, that it became clear that the complexity of human cognitive processes –particularly creative processes– cannot be reduced to descriptive or analytical observations. And I essentially agree with this: some might argue that a shortcoming of this project is its inability to fully explain the creative act from these perspectives. In response, I would argue that, after reviewing an extensive body of literature from various fields, I am convinced that no one has ever fully accomplished this, and perhaps no one ever will.

“the empirical studies of artists’ creative processes risk not doing justice to the particularity and variety of artistic practices by falling into reductionist abstractions”

Nevertheless, I believe the approach taken here remains valid, as it highlights another crucial aspect that emerges through research and reflection: the creative process for each piece reveals that all forms of creative thought –at least those discussed in this text– are intricately intertwined. These explorations systematically lead to one main point: while these processes may appear contrasting, and some may dominate in particular works, it is essential to understand them as three facets of the same entity.

One contribution of this project may lie in offering insights that highlight how the reality of the creative process extends far beyond any single paradigm. In this sense, the project finally aligns with the notion that any attempt to replicate the human creative process at an artistic level –such as through gen-AI– is likely to face significant challenges without a comprehensive integration of these three paradigms and possibly other aspects of human cognition that were not discussed in this project.

But, was this not obvious from the beginning? Not really.

A neurocognitive perspective

Some empirical support for this notion has emerged relatively recently in the field of cognitive neurosciences. * Cognitive neuroscience is a subfield of neuroscience that studies the biological processes that underlie human cognition, especially in regards to the relation between brain structures, activity, and cognitive functions. I didn’t directly discuss neuroscientific or cognitive neuroscientific insights because it would greatly extend the scope and length of this text and potentially deviate significantly from the artistic focus of the research. However, for some specific issues, it might be relevant to bring some insights from this field.

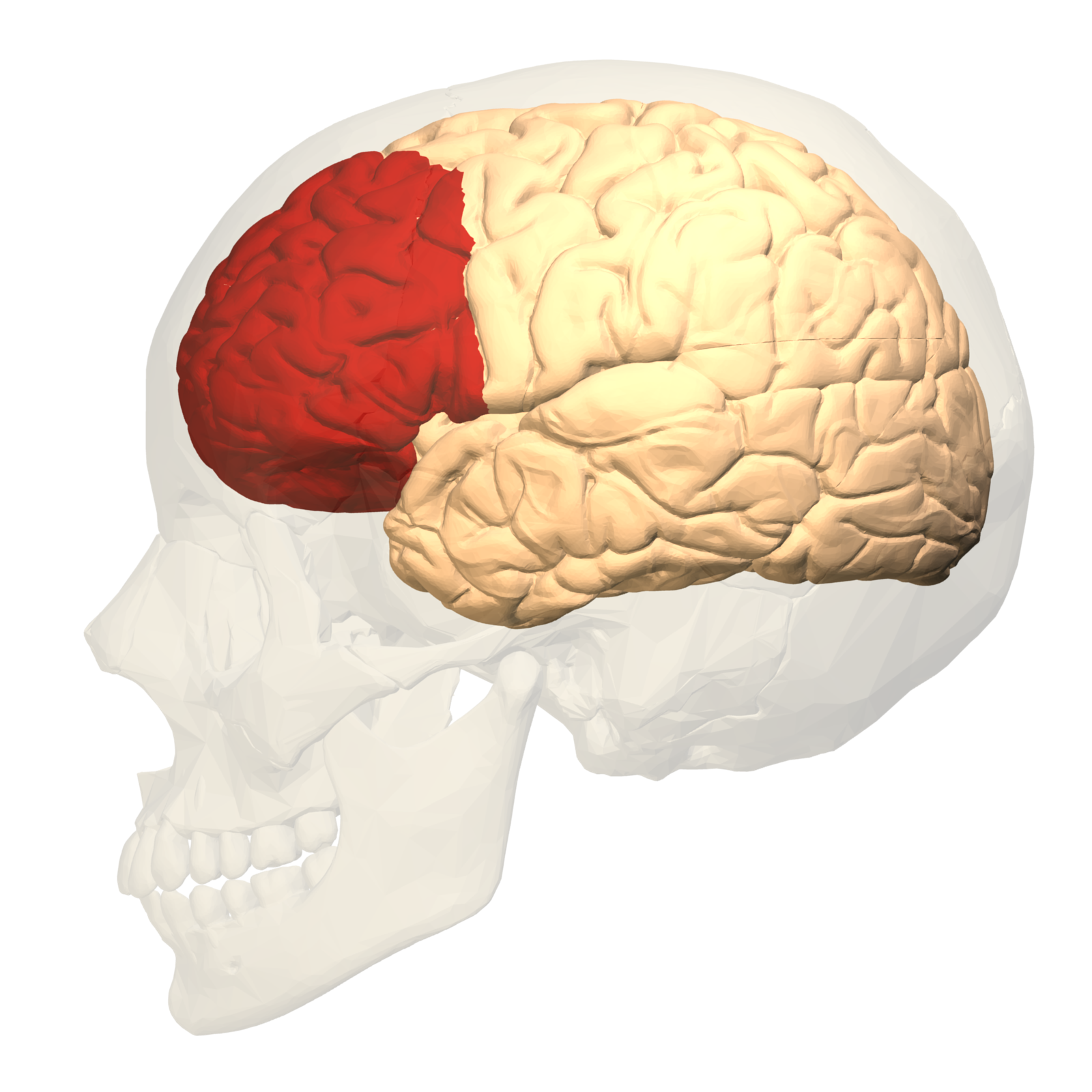

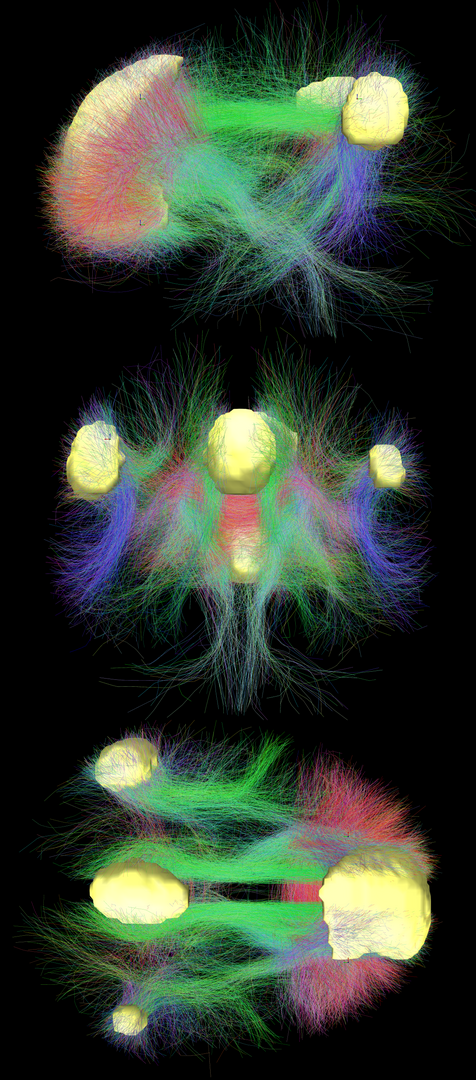

Essentially, there is some evidence that the neural processes that take place during the various stages of creative thinking tasks are characterized by frequent and rapid transitions between the brain’s networks responsible for spontaneous and deliberate thought. * Evangelia G. Chrysikou, "The Costs and Benefits of Cognitive Control for Creativity," in The Cambridge Handbook of the Neuroscience of Creativity, ed. Rex E. Jung and Oshin Vartanian, Cambridge Handbooks in Psychology (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018). The brain’s prefrontal cortex (PFC) seems to play a key role in this process: * Evangelia G. Chrysikou, "Creativity in and out of (cognitive) control," Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences 27 (2019). When the PFC is less active, as in tasks like instrumental improvisation or lyrics improvisation in freestyle rap, spontaneous creativity is enhanced by reducing inhibitory constraints and allowing stronger associative thinking. * Charles J. Limb and Allen R. Braun, "Neural substrates of spontaneous musical performance: An fMRI study of jazz improvisation," PLoS one 3, no. 2 (2008). ; Siyuan Liu et al., "Neural correlates of lyrical improvisation: an fMRI study of freestyle rap," Scientific reports 2, no. 1 (2012). In contrast, a more active PFC seems to support deliberate creative processes, helping individuals evaluate and select ideas based on context-specific goals.

In addition, some studies suggest that the generation of creative ideas is linked to increased functional connectivity between the PFC and the default mode network (DMN), a brain network mainly active during rest and associated with self-reflection and imaginative processes. * Roger E Beaty et al., "Default and executive network coupling supports creative idea production," Scientific reports 5, no. 1 (2015). Furthermore, some research indicates that the DMN plays a role in intuitive thinking by helping the brain make connections between seemingly unrelated pieces of sensory information. * Roger E Beaty et al., "Creativity and the default network: A functional connectivity analysis of the creative brain at rest," Neuropsychologia 64 (2014).

The problem with a solely cognitive or neuroscientific approach is that even if creative processes in the brain could be precisely mapped –identifying where they occur and which areas are involved– this does not necessarily explain the relationship between physical brain structures and creative thoughts, or between thoughts and broader conceptual frameworks. Cognitive neuroscience, simply put, is still far from resolving the distinction between brain and mind. *The problem of mind and brain, or mind and body for the sake of the argument, is a longstanding one, rooted in philosophical ideas from Plato, the distinction between body and soul in Aristotle and later Greek philosophers, and Descartes’ dualism, which separates the mind (or soul) from the body. Contemporary psychological trends generally agree that the mind emerges as an emergent property of the physical properties of the brain. However, the relationship between mental and physical properties remains a complex and debated topic. While modern psychology leans toward physicalism (the idea that the mind is a product of the brain’s physical processes), there are still diverse perspectives within the field. Neuropsychology explores the relationship between brain function and behavior, focusing on how specific areas of the brain are related to mental states. In cognitive science, the focus is more on understanding cognitive processes –such as perception, memory, and decision-making– through computational models, behavioral experiments, and other methods. While it does not always prioritize the precise neural mechanisms (the “how” and “where” in the brain), it recognizes that cognitive processes are rooted in the brain's functioning. Viewed from this perspective, the project offers valuable insights from an artistic research standpoint that aligns with recent cognitive and neuroscientific findings. I believe this, in itself, represents a meaningful contribution to the field –if not the most significant one, in addition to the artistic approaches and technical developments discussed throughout.

Further research grounded in creative practice and informed by cognitive theories could potentially help bridge this gap. For instance, a more focused artistic research project examining each individual cognitive paradigm and exploring its emergence in creative processes could provide more detailed and systematic descriptions and analyses, further connecting practice-based research with neurocognitive approaches. This project ultimately lacks that level of specificity.

Composition and institutionalization

At its core, creating music is a deeply sociocultural act, a truth that applies across most musical styles, genres, and trends –some shaped more by market dynamics, others by historical practices, and so on. In the field of WACM, the act of composing is deeply rooted in a longstanding institutionalized practice shaped by historical power dynamics, legitimations, directives, and stylistic premises. In this context, compositional decisions –whether rational, formalized, physical, or intuitive– are strongly influenced by the negotiation of meaning and value within cultural institutions, peers, and practitioners. The challenge in this sense is to rely solely on the notion of creativity to explain the process of composition fully. The most visible risk of institutionalization is that the label of “creative,” whether applied to a composer or a work of art, may stem more from negotiations of meaning and valuation within cultural institutions, often driven by the socio-cultural values and dominant political ideas of a given time or place.

Of course, composing can –and should– be regarded as a creative process: composers possess specialized skills that enable them to develop strategies of exploration, leading to novel, interesting, and valuable results. However, these explorations, ideas, insights, and creations are deeply rooted in a context, practice, and tradition that extend beyond individual subjective experiences. As I see it, this needs to be consciously reflected by anyone who aims to develop a practice within the field of WACM.

As Zembylas and Niederauer suggest, the term “creativity” risks becoming somewhat inflated in this context. * Zembylas and Niederauer, Composing Processes and Artistic Agency: Tacit Knowledge in Composing. Recognizing this could encourage composers to move away from some of these institutionalized practices, potentially exploring other musical traditions, art forms, cultural perspectives, functions, worldviews, or cosmogonies, if that aligns with their artistic or personal goals. While it is impossible to separate the creative act from its sociocultural implications completely, it is possible to observe some of these forces that, at first glance, may not be visible.

The borders of formalization

Music is a narrative shaped by multiple layers of operations that may indeed utilize formal systems for the generation, transformation, and organization of this narrative. In addition to this, creating music requires the intervention of tactile actions, sensory perceptions, and mental associations, possibly non-linear and chaotic. * In mathematics and science, a nonlinear system (or a non-linear system) is a system in which the change of the output is not proportional to the change of the input. Chaotic describes systems that, while deterministic, exhibit extreme sensitivity to initial conditions, leading to seemingly random and unpredictable behavior. Chaos often arises in non-linear systems and is characterized by patterns that are complex yet governed by underlying rules. Sources: "Nonlinear System," Wikipedia, last modified October 14, 2023 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nonlinear_system#cite_note-2 ; "Chaotic Systems," ScienceDirect, accessed December 30, 2024. https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/computer-science/chaotic-systems#:~:text=Chaotic%20systems%20refer%20to%20systems,as%20complex%20and%20unpredictable%20patterns Furthermore, these actions seem crucial to evaluate results and inform decisions within diverse frameworks in which a musical work might be conceived.

Formalizations of conventionally established or known compositional parameters usually operate at the level of conceptual representation; however, some of them are ultimately too complex for computational representation. Potentially, the interaction of these parameters with other formalized elements can become overwhelmingly complex. This ultimately prevents its symbolic representation into computationally operable forms –like numbers or strings.

“What in music is programmable? The answer might be: everything the composer knows about music. Question: what does the composer know about music? Or, better still: what does the composer know about himself when he composes? Whoever wants to program music ought to keep the answer to this question in mind.”

In this sense, the idea of formalization as a computational approach or “inside the system” became more a practical rather than foundational approach, local and strategic in its application. This idea finds some resonance with something proposed by the composer Horacio Vaggione: while music does leverage tools and knowledge from formal sciences, this formalization is not central to musical creation. In other words, computational systematization can aid in the creative process of composition but cannot completely substitute it.

Composers are concerned with the creation of musical situations emerging concretely out of critical interaction with their materials, including their algorithms. This task cannot be exhausted by a linear (a priori, non-interactive) problem-solving approach. Interaction is here matching an important feature of musical composition processes, giving room for the emergence of irreducible situations through non-linear interactions.

Procedural creative impulses and aesthetic foundations rooted in theory and practice remain present in intuition, even when they cannot be fully consciously expressed. Ultimately, I believe that artistic creation arises at the intersection of imagination, sensory perception, and formalization, and navigating this interplay remains an open question for me and possibly for every practitioner, especially in the field of CAC. Ideally, computers should not be seen as limiting but as tools for preserving and exploring the complexity and nuance inherent in musical ideas. When a computer facilitates this interplay between composer and system, it becomes artistically enriching and desirable. However, I remain skeptical about whether it is possible to fully explore the depths and nuances of musical creation using computers alone.

For the creative outcome of this project, engaging intuitively and embodying the results of computational formalizations and generative outcomes through a feedback process turned out to be essential. From my artistic perspective, this interaction consistently emerged as the space where the most interesting creative exchanges took place. Therefore, a potentially beneficial approach for composers could be to view this balance as a natural part of the creative process rather than allowing it to skew too heavily toward any of them. I acknowledge, however, that this is a highly personal perspective shaped by my own process and does not seek to question or label any approach or methodology as inherently right or wrong.

AI: Enemy or ally?

I believe that some of the technical developments in this project –which ultimately came as a natural consequence of the artistic inquiries– should be viewed as a voice speaking about how the encounter between humans, computers, and AI in the context of artistic practice can foster relevant artistic questions. And this is especially relevant in current times, where questions around gen-AI revolve around the replacement of the artist or even the end of art.

Technological advancements have always opened the door to new musical investigations. Initially, these advancements should be seen as opportunities to explore new creative processes and to reconsider fundamental notions such as technique, materiality, the role of the artist, and even the definition of art itself. It is also worth noting that this kind of paradigm shift has occurred many times throughout history. Even though we may not fully understand the depth of the paradigm shift that AI will bring to art practitioners –and ultimately to Humanity– I believe that it is possible to offer new visions and creative approaches to the emerging landscape while still maintaining a critical perspective.

Throughout this project, I have sought to highlight the pertinence and importance of AI methods from both conceptual and constructive perspectives, ensuring they serve as meaningful tools for expression. In other words, whenever I employed these methods, I engaged in deep reflection on their use and their connection to the message or intention of the artistic work. This process required me to repeatedly ask myself why I was using these tools, what they offered, and how they were artistically relevant. This continuous reflection contributed to reshaping my perspective on these methods along the process and helped me develop a critical view, which I believe is a significant outcome of the research process. I hope this attitude may inspire other artists to adopt a similar approach.