Multidisciplinary Insights

Chapter Overview

-

Music Composition

- Music as Communication

- Musical Material and Organization

- Extra-musical Material

- Musical Representation

- Musical Space

- Music Composition as an Artistic Research Practice

-

Cognition and Intelligence

- Consciousness vs. Unconsciousness

- Intuitive vs. Rational

- Human Creativity

- The Conceptual Level

- Heuristics and Formal Systems

-

Artificial Intelligence

- Similarities with Human Cognition

- Differences

In this chapter, I will first focus on topics related to music and composition, offering a personal perspective on key issues that contextualize the artistic outcomes of the project. Subsequently, I will address broad concepts and terminology related to cognition and creativity within the fields of cognitive and brain sciences. Following this, I will explore ideas from computation and AI. These two latter subsections primarily serve as literature reviews and conceptual overviews, providing a theoretical framework for discussing specific creative processes. While not exhaustive, they aim to establish the conceptual foundations needed to guide readers as the discussion becomes more specialized.

Music Composition

The artistic outcomes of this project primarily take the form of score-based musical compositions. These works are generally intended for performance by acoustic instruments or voices, often accompanied by a significant electronic component, either as fixed media or live electronics. Some pieces also incorporate other mediums, such as video and text. In this sense, my creative practice stems from the tradition of Western art music, particularly in forms of expression that emerged after the mid-20th century and continue to evolve today. This music is commonly referred to as Western art contemporary music (referred to hereafter as WACM). A significant portion of my workflow relies on computer-assisted composition (hereafter referred to as CAC) tools and methods. Historically, WACM and CAC have been closely connected, evolving in tandem, and it is widely recognized that WACM often encompasses practices related to CAC.

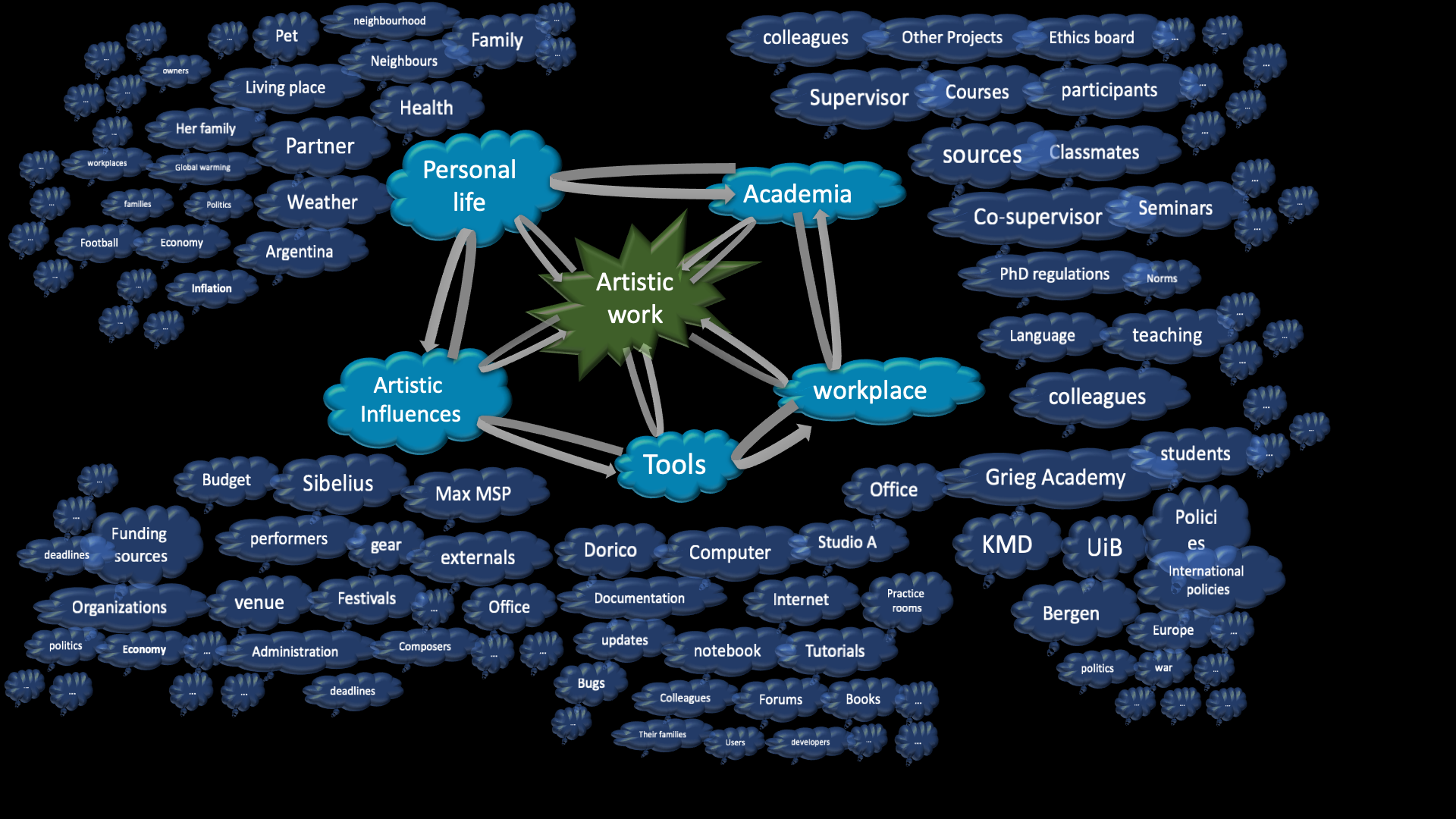

At the outset, I would like to define the scope of WACM composition as a culturally situated practice that I develop in a particular place and time in our world. Therefore, every creative act within this process relies not only on domain-specific (musical) decisions but also on physical spaces, political-economic contexts, societal and institutionalized * The institutionalization of art music dates back to the establishment of conservatories outside courts and churches in 17th-century Europe. By the mid-20th century, many states had created cultural apparatuses to support and guide musical creation through policies, subsidies, and commissions. Institutionalization not only conferred social recognition and legitimacy to established forms but also elevated the status of performers within these systems, often excluding practitioners outside these circles. It also introduced new categorizations of musical knowledge and economic models, with academic diplomas symbolizing prestige. This institutional focus, emphasizing notation and “score-based music,” has sometimes widened the gap between formally educated musicians and those trained through oral traditions. Western music and its contemporary practices became institutionalized earlier than other genres like jazz and folk, which followed later in the century. Today, still many musical expressions remain outside formal institutional structures. See Ingrid Le Gargasson, "The challenges of institutionalization of musical knowledge," Revue d’anthropologie des connaissances 14, no. 14-2 (2020). environments (institutions, teachers, colleagues, composers, performers, technicians, and many other agents), as well as artistic tools and materialities (paper, computers, software, sound, instruments, etc.).* See for example Alan Barclay, "Agency in compositional workflow: How you write affects what you write," Tempo (United Kingdom) 75, no. 296 (2021), https://doi.org/10.1017/S0040298220000960. In terms of agency, the influence of all actors within these networks* Actor-network theory (ANT) is a social theory method that asserts everything in the social and natural world exists within ever-changing networks of relationships, and nothing exists outside them. See Bruno Latour, Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory, (Oxford University Press, 2005). is potentially impossible to quantify or disentangle, and I do not intend to delve deeply into such disentanglement. However, I acknowledge the significant impact this network of agencies has on every aspect of my practice, from the smallest musical choices to long-term life decisions. I will address some contextual and ethical aspects of compositional practice later in this text.

I would like to begin discussing my creative practice by relating its common practical aspects to certain existing artistic practices. Within this project, composition is understood, first, in terms of timescales, as a long-term cognitive act. It is generally accepted to occur over long periods, differently from improvisation, although this distinction has been observed as a continuous spectrum of possibilities rather than a clear-cut separation.* The notion of “long-term” varies among different composers. However, the focus here is to highlight the distinction between real-time musical creation rather than exploring what “long-term” means to various composers or how this concept has been studied from a psychological perspective. See, for example, Nicolas Donin and Jacques Theureau, "Theoretical and methodological issues related to long-term creative cognition: The case of musical composition," Cognition, Technology and Work 9, no. 4 (2007), https://doi.org/10.1007/s10111-007-0082-z. Still, improvisation plays some role in some of my compositions, where performers are invited to improvise, usually following some guidelines (for example, in the final section of the piece I am a Strange Loop). Second, the act of composing yields some symbolic notation in the form of a score that should be performed by musicians. This score usually mediates between the piece as the result of my thought and the actual sound result. My scores may embody different forms, from detailed musical notation to written instructions.

I believe that music composition involves the organization of sound. As a time-based sonic art, this organization unfolds by structuring sound over time to create categories of meaning.* A concise definition of meaning is 'what something expresses or represents.' in Cambridge Dictionary Online, s.v. “Meaning,” accessed Oct. 27, 2024, https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/meaning. These categories emerge through the relationships, significances, or sensations that organized sound conveys, which are interpreted through context, intent, and subjectivity. Musical organization, therefore, can be understood as the structuring and systematizing of sonic phenomena into a clear, defined, and often standardized framework –a concept closely tied to formalization,* A concise definition of formalization is 'the act of giving something a fixed structure or form by introducing rules' in Oxford Learner's Dictionaries. "Formalization." Oxford Learner's Dictionaries. Accessed December 30, 2024, https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/definition/english/formalization. which I will address later.

“A composer is an architect in sound, time, space, and flux.”

Music as communication

My creative processes usually begin with a question, an inquiry –or perhaps a series of them. The purpose of the artwork, then, becomes responding to those questions from a creative standpoint. At the core, these inquiries emerge fundamentally from a desire to convey something: a personal longing for a form of interhuman expressive connection. Essentially, I view the act of music composition as a communicative act.* The first person from whom I took this idea is the Italian composer Luca Belcastro, who spent many years working among Latin American composers aiming to construct networks of collaboration between peers around the continent. I owe him enormous gratitude for his great teachings and his generosity.

“Man, in addition to relating to the natural world, absorbing the reality in which he lives, relates to himself, with his own sensitivity, his needs, curiosities, and emotions. For this reason and for the fact that it is a social animal, an innate demand invites it to share its inner world with others, with the society in which it finds itself. From all this arises the desire and need for a communicative act.”

Initially, my ideas in this regard stem from a two-folded ground. On the one hand, the many parallels that exist between music and language have led many authors to argue in favor of a common evolutionary origin: music, as a human evolutive trait, has been linked to a proto-linguistic form of communication.* The literature on this topic is vast, but some very influential reading for me have been Aniruddh D. Patel, Music, Language, and the Brain (New York: Oxford University Press, Incorporated, 2007), Ray Jackendoff, "Parallels and Nonparallels between Language and Music," Music Perception: An Interdisciplinary Journal 26, no. 3 (2009), https://doi.org/10.1525/mp.2009.26.3.195. See also Mengxia Yu et al., "The shared neural basis of music and language," Neuroscience 357 (2017), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2017.06.003, On the other hand, its longstanding existence within human societies has provided it with the capacity of music to encapsulate meaning that can be effectively shared between individuals and groups.

“A composer is someone who exists in a creative dialog with the context and material and develops ways to represent his/her thoughts.”

But meaning encompasses not only propositional, logical-symbolic, rationalizable, or verbalizable representations. It also involves sensuous appreciations that sometimes cannot be directly related to a form of rational or conscious thought. In particular, musical meaning involves essentially aesthetic judgments based on unconscious and emotional experiences.* A detailed discussion of the italicized words will follow in the next subsection, ‘Cognition and Intelligence’. In this sense, I view the nature of music as dual, consisting of a complex combination of abstract formalizations –which, most of the time, deal with more or less complex structures and forms of sonic temporal organization– with sensuous forms, mainly related to aesthetic and emotional experiences.

“Music is not the mere vehicle for the transmission of conceptual content, however, but rather a direct object of sensuous appreciation—with listeners enjoying some harmonies more than others, finding some rhythms fascinating and others not, and reveling in the sheer sonic beauty of instrumental timbres.”

The need for communication sparks the work and leads it toward points of interest that I consider relevant to express: what I want to talk about. In this sense, there isn’t a unique topic my music speaks about. Rather, each piece says different things. Maybe some common aura might be perceived as encompassing them: I am very interested in the interplay between mankind, nature, and technology. Of course, these are three huge overarching themes that have been the focus of possibly all the artistic productions in History, leaving aside religion and religious issues (since as I am not a religious person, I don’t have a strong connection with these). My artistic interests are mainly centered around the relationship between these themes, especially in today’s world. I am particularly interested in using my work to explore and respond to current societal and political issues. Additionally, my works are curious about sonic and musical translations of natural phenomena and natural processes and potentially discovering some aesthetical value in these representations.

Musical material and organization

The discussion around musical material is a dense one. Musical material refers to the set of sonic elements that serve as the starting point for composing a musical work. Within my work, musical material is conceived in relation to its semiotic dimensions: as a vehicle of meaning and as a building block for a musical message. In this context, the term semiotics refers to the study of music as a system of signs, encompassing its creation, perception, and interpretation within cultural and symbolic contexts.* Especially relevant have been the readings in Jean-Jacques Nattiez, Music and Discourse: Toward a Semiology of Music (Princeton University Press, 1990), Christopher Small, Musicking: The Meanings of Performing and Listening (Wesleyan University Press, 1998), and Steven Feld, Sound and Sentiment: Birds, Weeping, Poetics, and Song in Kaluli Expression (Duke University Press, 2012).

There are two main discussions around the idea of musical material that are important in my work. On the one hand, the discussion around historical musical material and how musical elements from different historical contexts are used as material in new music.* See for example George Rochberg and William Bolcom, The Aesthetics of Survival: A Composer's View of Twentieth-Century Music (Ann Arbor, United States: University of Michigan Press, 1984). On the other hand, the discussions around advanced material which is not only technically complex but also resistant to popularization, commercialization, and immediate comprehension.* Theodor Adorno, Philosophy of New Music (University of Minnesota Press, 2006). These two have been quite influential in my musical education and past practice.

“As in society, temporal structures in a composition are formed by way of memory. The memories brought forth, inherent in the musical material, also form a relationship to the memory of the place of production. In this sense, musical material pre-exists, as it forms a dialogue with the material conditions of its production, the composer re-collecting this material within the compositional process.”

There is always a trace of extra-musical meaning in my material. For me, musical material is often linked to the representation of something beyond itself, something external to its phenomenology. This does not imply that my choice of material is free from aesthetic judgments rooted in its sonic qualities –those are always present to some degree. However, in my practice, considerations of musical material are typically driven by conceptual connections.

“Sound is just a surface. The fetishization of sound reduces the responsibility to the musical material.”

Even though my musical material is usually charged with some extra-musical meaning, my music is not devoid of semi-autonomic* The concept of “music autonomy” is a broad one, initially associated with Eduard Hanslick's idea of music as independent of external narratives or emotions (see Mark Evan Bonds, "Robert Zimmermann's 1854 Review of On the Musically Beautiful: A Translation and Commentary," in The Aesthetic Legacy of Eduard Hanslick (Routledge, 2024)). However, post-structuralist theorists have long argued that music cannot truly be autonomous, as it is inherently tied to cultural and social narratives (see, for example, Susan McClary, Feminine Endings: Music, Gender, and Sexuality (University of Minnesota Press, 2002)). In this context, the term “autonomy” may seem outdated. I prefer to use the term “semi-autonomy,” which refers to describe a type of musical organization that does not directly connect to an extra-musical narrative, such as a text or poem that dictates certain musical choices. Instead, a semi-autonomous musical organization emphasizes compositional developments which, of course, are always ultimately shaped by social and cultural norms and constrained by the pursuit of particular musical results. However, they are somehow detached —if this is ever truly possible— from the extramusical origin of the material. musical organization. In my music, the interplay between meaning, referentiality, and semi-autonomy is very dynamic and ever-changing; each piece develops its own criteria for balancing these elements. Perhaps a good example to understand what I mean here is the piece Versificator – Render 3. In it, the musical material consists of speech sounds, including nonsensical words in an imagined language. Conceptually, this is relatively easy to connect with the metaphor for the Versificator machine in Orwell's 1984.* Gerge Orwell, 1984 (Biblios, 2023) However, the organization of the material in time is mainly sound-based –or semi-autonomic from its extramusical background. The extra-musical connection that the material somehow traces usually remains as a loose metaphor and does not necessarily interfere with the musical logic of the compositional processes.

Extra-musical material

Music can coexist with or be conceived as part of a unified multimedia work. My musical thought is open to the inclusion of non-sonic mediums and spatial considerations, and it usually does so. This is particularly evident in the piece Oscillations, where music coexists with video projections.

The idea of music coexisting with visual elements has a long tradition in WACM, especially in opera and opera-related works, where musical narratives are intertwined with staging and visual storytelling. However, different –and interesting– examples of music integrating visual aspects can be found in the works of composers such as Mauricio Kagel and Dieter Schnebel. These two composers –whose work has profoundly influenced me– are often associated with instrumental musical theater or composed theater.* Matthias Rebstock and David Roesner, Composed Theatre (Intellect, 2012). In this tradition, visual elements are composed or conceptualized from a musical perspective. Furthermore, there is a large and growing field of practitioners within a domain known as “visual music”.* See for example Brian Evans, "Foundations of a Visual Music," Computer Music Journal 29, no. 4 (2005), http://www.jstor.org/stable/3681478 One notable practitioner in this field is the Argentine composer Ricardo Dal Farra.

Even though in my practice, music almost always exists in interplay with other artistic mediums, I think musically, and I conceive my artistic narrative initially from a sonic perspective. Recently, however, I have faced some challenges to this way of creating, with the adoption in my practice of other than sonic mediums, such as algorithmic poetry and text. The nature of those challenges mainly has to do with difficulties in creating and integrating the two mediums into a common narrative, and for the first time, somehow, I have seen myself thinking more as a writer than as a composer.

Musical representation

My music is mainly score-based. This means that it is represented symbolically as a system of signs that equate to certain sonic parameters that are deemed as musical. Symbolic musical information, thus, refers to the representation of music typically using notation systems, such as the conventional musical score that stems from the Western tradition.

There exists, however, another important dimension of symbolic representation of my music in connection with electronic music and CAC. This system is mainly based on the representation of musical parameters in a language that computers can understand: numbers.* Historically, the most representative example of numerical musical formalization might be the MIDI protocol, which encodes pitch, duration, and velocity (dynamics) —among other metadata— into a computational representation in the form of binary numbers (bits and bytes). In computer-assisted composition workflows, numerical representations of musical parameters are often used to generate, manipulate, and control musical material and processes. I define this process of numeric representation of musical parameters to be operationalized computationally as formalization. However, formalization also occurs outside the computer, or “outside the system,” as these numeric systems usually fall short of encompassing all the possible musical dimensions involved in the creation of music, or the complexity of the processes involved in these acts it is not easily represented as computational expressions. Balancing musical representation, formalization, and communication is a crucial aspect I reflect on throughout my works.

Musical Space

Music happens in time. But also happens in space. The use of space for musical purposes has been a common practice since the Middle Ages and even before. Currently, the use of multiple speakers and sonic immersive spaces is relatively common in WACM. My work is not an exception to this. Even though my research does not delve into technical developments or even too deep into the usage of spatialization paradigms, the dimension of space is always present in the works.

The idea of musical space relates to my idea that music, when possible, benefits from a fully immersive experience. I have discussed this already concerning visual music and instrumental theater. Not only sound, video, and text can enhance a musical experience. Space, in addition, has the potential to give music a stronger communicational capacity. From triggering strong spatio-temporal associations in the listener to experiencing emotional or even physical sensations.

This is visible in my work Oscillations, where I use soundscapes.* The term 'soundscape' gained popularity through the writings of R. Murray Schaffer and is generally understood as an acoustic environment, often associated with cities, nature, or specific eras See R. Murray Schafer, The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment and the Tuning of the World (Simon and Schuster, 1993), 111. as a means to immerse a listener into a different space, or time context –primarily connected to the wintry landscape of Schubert-Muller’s Winterreise– but also into another space-time connected to personal past recollections and imagination. While a soundscape is not inherently tied to a musical context, it can be used musically, as demonstrated in the works of Pierre Schaeffer and John Cage. However, the idea of soundscapes as non-musical sonic spaces raises questions about the boundaries between music, sound, noise, among many others. Addressing them would exceed the scope of this reflection. I adopt Murray Schafer’s perspective, viewing the soundscape as a blurring of the edges between music and environmental sounds.

I mainly use the Ambisonics spatialization paradigm.* David G. Malham and Anthony Myatt, "3-D Sound Spatialization using Ambisonic Techniques," Computer Music Journal 19, no. 4 (1995), https://doi.org/10.2307/3680991 . Ambisonics is a spatial audio technique that captures, represents, and reproduces a three-dimensional sound field, allowing listeners to experience sound from all directions with precise localization. However, a deep or too technical discussion on sound and music spatializaion should be not expected, as it is not my strongest knowledge or focus.

Music composition as an artistic research practice

I understand the act of music composition as a process of artistic research. The question of composition as research has been broadly discussed, mainly from two antagonistic theses. The first claims that viewing musical composition as a form of research is a category error. Although there exists some previous writing on the matter, I will mainly refer to an article by the composer John Croft* John Croft, "Composition is not research," Tempo (United Kingdom) 69, no. 272 (2015): 8, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0040298214000989. that became quite controversial and got several responses, as well as responses to these responses.* See for example Ian Pace, "Composition and performance can be and often have been research," Tempo (United Kingdom) 70, no. 275 (2015), https://doi.org/10.1017/S0040298215000637; Candem Reeves, "Composition, research and pseudo-science: A response to John Croft," Tempo (United Kingdom) 70, no. 275 (2016), and a response to these responses, in John Croft, "Composition, researching and ways of talking," Tempo (United Kingdom) 70, no. 275 (2016). The whole discussion around it encompasses several dimensions, such as philosophical, methodological, and ethical, and I believe that it greatly contributes to clarifying why I believe that music composition should be understood as a research practice.

The defenders of the idea that music composition is not research argue reasons firstly relying on methodological inconsistencies with established academic research practices, such as the inutility of posing research questions or the fact that the outcome of composing is not generalizable, non-verifiable, and non-descriptive; secondly, a fundamentally philosophical understanding of artistic processes and their cognitive content as resistant to conceptualization: presents rather than represents, discloses without describing, (as) such things can only be shown, not told.* Croft, "Composition is not research," 8. These authors propose that the cause for this miscategorization is the fact that, after being forcefully migrated to the world of universities, these practices were required to conform to academic regulations, including research protocols that initially were alien to them. In their opinion, composition as research is a symptom of the hollowed-out instrumentalism of academia today, and this is harmful to genuine musical originality.

These claims can and have been challenged. To begin with, they seem to depart from the assumption that scientific research and its methods are the only valid research paradigm, and thus, artistic practices that, of course, don’t fit in should not be regarded as research. In this sense, the literature about research in humanities has already widely discussed the distinction between research in art and science, and fundamentally, the literature on artistic research has discussed extensively problems such as the production of knowledge in art, the role of the artistic practice in academia, and many other relevant issues that Croft –and others– seems to be unaware of.* See for example Henk Borgdorff, "The production of knowledge in artistic research," in The Routledge Companion to Research in the Arts (2010); Henk Borgdorff, The Conflict of the Faculties. Perspectives on Artistic Research and Academia, (Leiden University Press, 2012), https://doi.org/10.26530/oapen_595042; Nina Malterud, "Artistic research – necessary and challenging," Nordic journal of art and research, no. 1 (2012).

“We must be able to discuss not only scientific knowledge but also the one that is created and formulated through the arts. And since the sensuous or artistic knowledge is of another type than the scientific, we have to develop another way of discussing it. We have to develop an epistemology for the arts –an aesthetics, Baumgarten would say – new concepts and theories with which we can grasp that other way of knowing that we meet in the arts and the methods and practices that go into its creation.”

Regarding the question of the methodological process, more precisely, about posing research questions, I am inclined to believe that proceeding this way is a personal choice and surely not right or wrong, but when one chooses to do it, it is obvious that responses to these questions that are not self-evident. It is possible to proceed by formulating theoretical or aesthetical assumptions –which could be very well posed as hypotheses– and the purpose of this compositional practice is to assess their sounding result, either confirming or refuting them –ideally– through an aesthetic judgment. Compositional inquiries expressed as research questions are answered through compositional practice, and doing so is a complex process that involves significant research efforts. Arriving at a resulting outcome is usually not a self-evident task, as it may involve multiple and multifaceted possibilities.

It is fair to say at last that, for me, musical decisions should not be subject to empirical claims like scientific research. However, this doesn’t mean composition lacks evidence or criteria; research results in music can also be open to correction and refutation. Therefore, it is reasonable to expect that composers can articulate their inquiries, objectives, stages, and reflections. This articulation can inform others pursuing similar inquiries. Complementary to the idea of another way of knowing in artistic research, I believe that it is beneficial for composers to communicate how their work is constructed and why it is valuable, as this might contribute to the broader knowledge within the field.

“Artistic research in the emphatic sense […] unites the artistic and the academic in an enterprise that impacts both domains. Art thereby transcends its former limits, aiming through the research to contribute to thinking and understanding; academia, for its part, opens up its boundaries to forms of thinking and understanding that are interwoven with artistic practices.”

Approaching composition from an investigative point of view –as I believe has been the case for this project– is one approach rather than a categorical definition of what it means for composition to be artistic research. Within music, and especially composition, there are many different perspectives on what this process entails.* See for example Hakan Ulus, Cosima Linke, and Jörn Peter Hiekel, "Künstlerische Forschung," Musik & Ästhetik 28, no. 112 (2024). https://www.musikundaesthetik.de/article/99.120205/mu-28-4-82. Ultimately, in each of my compositions, an underlying inquisitive motivation is present, along with a desire to articulate technical and methodological aspects, develop potential contributions to the field, and explore more reflexive dimensions connected to the reception and social context of the work. I am hopeful that some might find my approach worthwhile as an artistic research practice.