Cognition and Intelligence

Cognition and Intelligence are essentially two different things. On the one hand, cognition is defined as:

“the mental action or process of acquiring knowledge and understanding through thought, experience, and the senses. […] It is in essence, the ability to perceive and react, process and understand, store and retrieve information, make decisions and produce appropriate responses.”

Intelligence, on the other hand, is defined as:

“A mental quality consisting of the abilities to learn from experience, adapt to new situations, understand and handle abstract concepts, and use knowledge to manipulate one’s environment.”

Essentially, cognition encompasses the processes of information, while intelligence represents the capacity to effectively use it. Broadly speaking, cognition can be exhibited not only by humans but also by other life forms and even technological artifacts.* See for example N. Katherine Hayles, "Cognitive Assemblages: Technical Agency and Human Interactions," Critical Inquiry 43, no. 1 (2016), https://doi.org/10.1086/688293, and Andy Clark Natural-Born Cyborgs: Minds, Technologies, and the Future of Human Intelligence (Oxford University Press, 2004).

Within the field of psychology, there are three main approaches to contemporary cognitive theory. The first is the information-processing approach, which compares the human mind to a sophisticated computer system designed to acquire, process, store, and use information. This paradigm is widely known as cognitivism. The second paradigm draws inspiration from the structural design of the brain, specifically focusing on the connectivity patterns among neurons. This theoretical approach is known as connectionism. Essentially, it views the mind as a vast pattern recognition system that learns and constantly adjusts itself based on sensory input data. A third component of the overall framework of human cognition is the embodied perspective. This approach argues that cognition is not merely the product of internal mental processes but is deeply intertwined with sensory-motor experiences and interactions with the environment.

These three paradigms form the primary categorical distinctions in the study of human cognition. In the following chapters, I examine each in greater detail, relating them to the creative processes for each of the works that constitute the artistic outcome of this project. Before exploring these paradigms further, however, it is essential to address some foundational concepts. I begin with a central dichotomy in cognition, with deep implications for creative processes: the distinction between conscious and unconscious cognition.

Consciousness vs. Unconsciousness

Consciousness is defined as the state of being aware of and responsive to one’s surroundings.* Oxford English Dictionary, "consciousness, n," in Oxford English Dictionary (Oxford University Press, 2024). However, since ancient times, consciousness has been the subject of study, analyses, explanations, and large philosophical, scientific, and even religious debates. There are multiple opinions and approaches on what is or should be considered consciousness or even what exactly needs to be studied to better understand it. As my background and my research interest come mainly from the perspective of psychology and cognitive sciences, I will narrow down the discussion to theories of consciousness within this field.

The primary manifestation of consciousness is rooted in the distinction between the self and the environment. Consciousness involves a state characterized by sensations, emotions, volition, and thought. While consciousness and the concept of mind are strongly interconnected, they are often viewed as distinct entities. The mind represents the content of our experiences, while consciousness is the perceiver of these experiences. Consciousness, then, refers to the unchanging and continuous aspect of our experience, while the mind is ever-changing. Some authors use the analogy of a movie theater to illustrate this distinction, where the mind is akin to the content of the film, and consciousness is the screen upon which the movie is projected.* See for example the work of Daniel Dennett in Ch. 4, in Susan Blackmore, Consciousness: an introduction, 2nd edition (Oxford University Press, 2011).

On the other hand, psychologists and cognitive scientists generally agree on the existence of an unconscious mind. Daniel Kahneman, for example, distinguishes between two types of mental processes: fast activities, which are primarily automatic and effortless, and slow activities, which are deliberate, effortful, and associated with subjective experiences of agency, choice, and concentration.* Daniel Kahneman, Thinking, fast and slow (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011). Kahneman’s two systems roughly correspond to conscious and unconscious processes. A further refinement of this duality is found in the dual-process theory, which describes human information processing through two main cognitive modes: Type 1, which is fast, automatic, and handles large volumes of data intuitively, and Type 2, which is slow, deliberate, and processes information sequentially in a more effortful manner with limited capacity.* "The duality of mind: An historical perspective," in In Two Minds: Dual Processes and Beyond, ed. Keith Frankish and Jonathan Evans (Oxford, 2009; online edn, Oxford Academic, 22 Mar. 2012), https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199230167.003.0001 .

The classic literature on unconscious cognition suggests that this type of processing arises from subliminal perception, where stimuli are detected without conscious attention.* Attention is a pillar concept in the field of cognition and brain sciences. It is defined as a state in which cognitive resources are focused on certain aspects of the environment rather than on others and the central nervous system is in a state of readiness to respond to stimuli. Since humans have a limited capacity for attention, focusing on certain stimuli at the expense of others, much of the research in this field has focused on understanding the factors that influence attention and the neural mechanisms behind selective information processing. “Attention” in Gary R. Vandenbos, APA Dictionary of Psychology, American Psychological Association (2007). Researchers studying unconscious cognition often examine how memory traces of these unattended stimuli influence cognition and behavior, even when individuals cannot consciously recall the experiences. From this perspective, unconscious cognition is typically viewed as having limited analytical capabilities, contributing less information to our conscious experience compared to to consciously perceived stimuli.* Anthony G. Greenwald, "New Look 3: Unconscious cognition reclaimed," American Psychologist 47, no. 6 (1992), https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.47.6.766 .

However, contemporary research trends regarding unconscious cognition have proposed an alternative perspective that acknowledges the unconscious as a sophisticated and adaptive guidance system. Some authors argue against equating the unconscious mind solely with subliminal processing, citing evidence of complex judgmental and behavioral phenomena that operate outside direct conscious awareness. In this view, an unconscious goal pursuit, influenced by evolutionary motives, operates similarly to a conscious goal pursuit. The contemporary model of unconscious cognition emphasizes the role of genes, culture, and early learning in shaping unconscious processes.* John A. Bargh and Ezequiel Morsella, "The Unconscious Mind" Perspectives on Psychological Science 3, no. 1 (2008), https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6916.2008.00064.x .

According to K. Hayles, potentially the most important function of unconscious cognition is:

“to keep consciousness, with its slow uptake and its limited processing ability, from being overwhelmed with the floods of exterior and interior information streaming into the brain every millisecond.”

Following this line of thought, it seems like the distinction between conscious and unconscious thought is essentially connected to intentionality. We have intention over our conscious thought, but we lack it over our unconscious. I believe that this statement is somehow familiar to art practitioners when discussing certain practices that involve a lack of intentionality or a lack of reasoning. In particular, when we discuss art creation as an intuitive practice. But what is intuition?

Intuitive vs. Rational

The intuitive and the rational are two terms that are probably familiar to every art practitioner. The rational is often associated with logical reasoning and step-by-step calculations to solve well-defined problems, relying on explicit, conscious thought processes. Intuition, on the other hand, involves arriving at conclusions or insights without explicit reasoning. It often feels like an immediate awareness of a solution, idea, or decision. While the rational is closely linked to intelligence, characterized by the deliberate and systematic application of knowledge, the intuitive remains more elusive and harder to define.

Intuition is a form of cognition. Chassy and Gobet have proposed a list of key criteria for determining it: (1) rapid perception and understanding of the situation at hand, (2) lack of awareness of the processes involved, (3) holistic understanding of the problem situation, (4) the fact that experts’ decisions are better than novices’ even when they are made without analytical means, and (5) concomitant presence of emotional coloring.* Philippe Chassy and Fernand Gobet, "A hypothesis about the biological basis of expert intuition," Review of General Psychology 15, no. 3 (2011), https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023958. Ultimately, intuition can be understood as the intersection of perception, knowledge, and emotions, acting as a bridge between situational, bodily knowledge and unconscious understanding.

There are two primary categories of theories on intuition. The first explains it from a mechanistic perspective, focusing on specific cognitive mechanisms and processes such as pattern recognition and chunking.*In cognitive psychology, chunking is a process by which small individual pieces of information are bound together to create a meaningful whole later on in memory. For example, when we group numbers by two or three to easily remember a phone number. According to this view, experts acquire a large number of perceptual patterns (or "chunks") that help them make rapid and intuitive decisions.* Fernand Gobet and Herbert A. Simon, "Five Seconds or Sixty? Presentation Time in Expert Memory," Cognitive Science 24, no. 4 (2000), https://doi.org/10.1207/s15516709cog2404_4 . Chassy and Gobet further extended this framework by introducing the concept of templates, which are more complex memory structures enabling experts to rapidly and holistically understand situations.* Templates are a special type of chunk that possess both a core, made of stable information, and slots, made of variable information. For example, if we think of the template of a “room” the fact that rooms have a floor, a ceiling, and walls, would constitute the core, whereas the number of doors and windows would be encoded as variables. In Philippe Chassy and Fernand Gobet, "A hypothesis about the biological basis of expert intuition," 200. The second category emphasizes the development of intuition through experience, context, and holistic understanding. This theory suggests that intuition evolves as individuals progress from novices to experts, with increasing experience leading to a more fluid and intuitive grasp of situations, without relying on the detailed mechanistic explanations of the first category.* H. Dreyfus, S.E. Dreyfus, and T. Athanasiou, Mind Over Machine (Simon & Schuster, 1986).

Emotions play a crucial role in intuition, as Chassy and Gobet suggest. When individuals acquire expertise, they not only develop perceptual chunks but also learn which elements are beneficial, harmful, or neutral to their task. These chunks are associated with emotional responses, such as reward or punishment, which are integrated into memory structures. As a result, emotional relevance is recalculated when new items are chunked together. In future situations, these emotional responses help focus attention on the most useful chunks, guiding intuitive decision-making by steering individuals toward certain solutions over others.* Philippe Chassy and Fernand Gobet, "A hypothesis about the biological basis of expert intuition."

Certain artistic practices, especially those outside academic or institutionalized contexts, are often described as rooted in intuitive knowledge. The development of expertise in these areas is typically linked to extended exposure to a particular way of doing, which doesn’t necessarily involve a rational approach or learning a system of rules, principles, or axioms governing those practices. However, certain other practices –and, in particular, the case of music composition is a good example of this– are discussed as potentially relying on two antagonistic approaches: on the one hand, an intuitive approach, and on the other hand, an approach focused more on strategic and structural aspects. This dichotomy, however, is posed more as a continuum or spectrum rather than a clear-cut dichotomy.* Geraint A. Wiggins, "Defining inspiration? Modelling the non-conscious creative process," in The Act of Musical Composition: Studies in the Creative Process (Routledge, 2012).

In any case, whether driven by intuitive or rational approaches, art practicioners are usually labeled as creative. But what does creativity mean?

Human Creativity

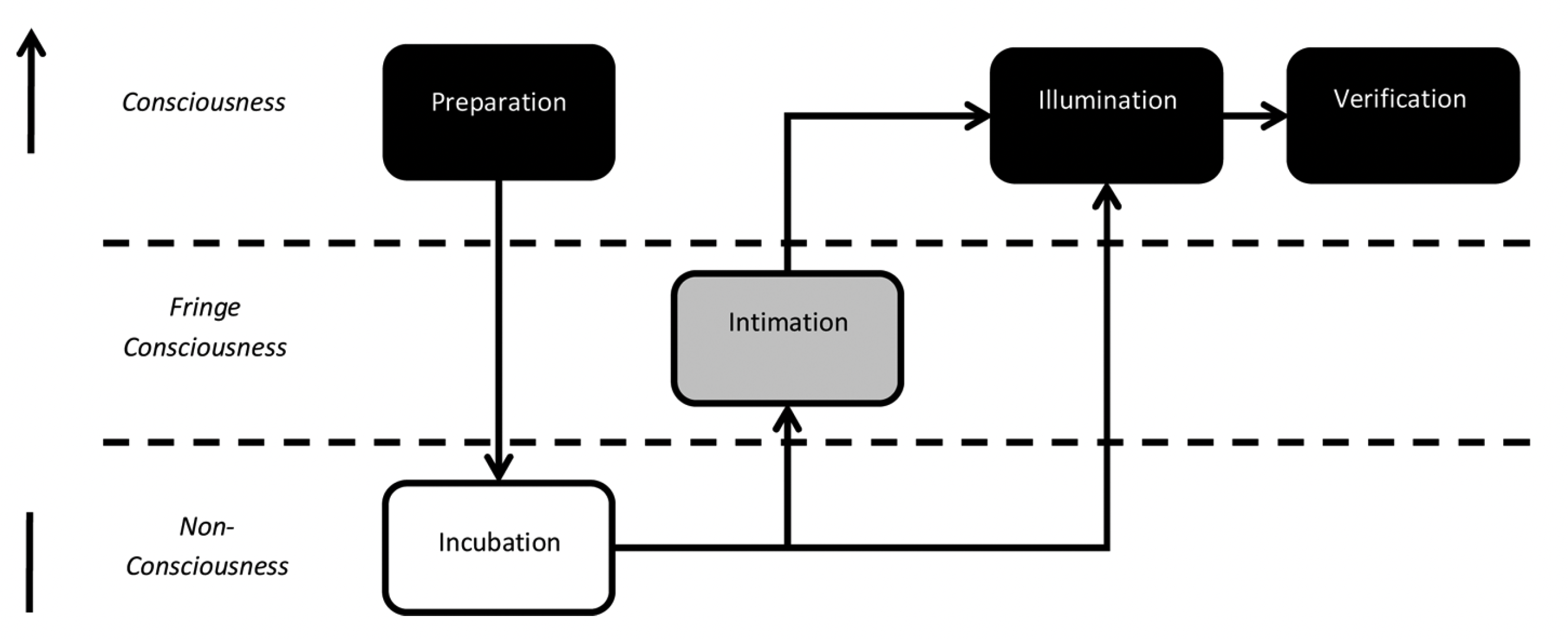

Creativity has been defined as the ability to come up with ideas or artefacts that are new, surprising and valuable.* Boden, The creative mind: myths and mechanisms, 1. In particular, when we speak about creativity in art, the ideas about conscious and unconscious processes, or rational and intuitive, have a long-standing presence in the discourse. For example, the classic model of creativity by Graham Wallas already differentiated between conscious and unconscious thought processes within his well-known four stages: preparation, incubation, illumination, and verification.* Graham Wallas, The art of thought (Brace Harcourt, 1926). In some of these stages, there is deliberate control over the thought process, and that control is totally or partially absent in others. Further refinements to this model have proposed a version of it with three levels of proximity to consciousness (nonconsciousness, fringe consciousness, consciousness) and five stages (Preparation, Incubation, Intimation, Illumination, and Verification).* Eugene Sadler-Smith, "Wallas’ Four-Stage Model of the Creative Process: More Than Meets the Eye?" Creativity Research Journal 27, no. 4 (2015), https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2015.1087277 .

The topic of human creativity is extensive and multifaceted and can be approached from several fields, such as psychology, sociology, philosophy, or even computation. This complexity derives mainly from two perspectives. First, from the discussion of what counts as a creative idea.* See for example Ch. 11 in Boden, The creative mind: myths and mechanisms. In this sense, creativity is viewed as a contextually embedded phenomenon,* Ana Camargo et al., "Cultural Perspectives on Creativity," in The Cambridge Handbook of Creativity, ed. James C. Kaufman and Robert J. Sternberg, Cambridge Handbooks in Psychology (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019). and as such, creative acts are viewed as creative, novel, or valuable depending on the social context in which they are embedded. Second, from the complexity around identifying the mental processes –and its neural basis– that produce those ideas.

Historically, the study of creativity has been focused on the relationship between creative behavior and intelligence or personality. However, in recent times, the focus on studying creativity has switched to a sociocultural approach. This view emphasizes that creative processes are not solely individual but are distributed across people, objects, places, and institutions. Ultimately, the study of human creativity has led to the recent development of frameworks by cultural and sociocultural psychologists that acknowledge its simultaneous psychological and cultural nature.

I believe that this question is crucial, especially in the context of music creation, and specifically WACM: The relationship between music composition an intra-personal act versus a contextually embedded phenomenon shaped by institutional forces, social capital, and even economic and political factors. What follows aims to bridge these two approaches by looking into creativity as an intra-personal exploration within socially constructed spaces of thought: conceptual spaces. In order to do that, I must first address an important topic: the conceptual level.

The Conceptual Level

The issue of how concepts and categories are represented and organized in our minds is a major challenge in cognitive science. A proposed solution to this problem is the idea of conceptual spaces, introduced by Peter Gärdenfors.* Peter Gärdenfors, "Conceptual Spaces: The Geometry of Thought (The MIT Press, 2000), https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/2076.001.0001 . This theory essentially portrays the human mind as a geographical space in which concepts are organized by proximity. The idea of conceptual space posits that concepts are not rigid categories with defined boundaries. Instead, they are multi-dimensional spaces –or regions– within a cognitive domain.

The construction of these spaces is based on perceptual and cognitive attributes relevant to a particular concept. Therefore, concepts are not represented as individual symbols or set categories but rather as geometric configurations within a multi-dimensional space that exists in the mind. Each dimension represents a distinct quality or property relating to the concept.

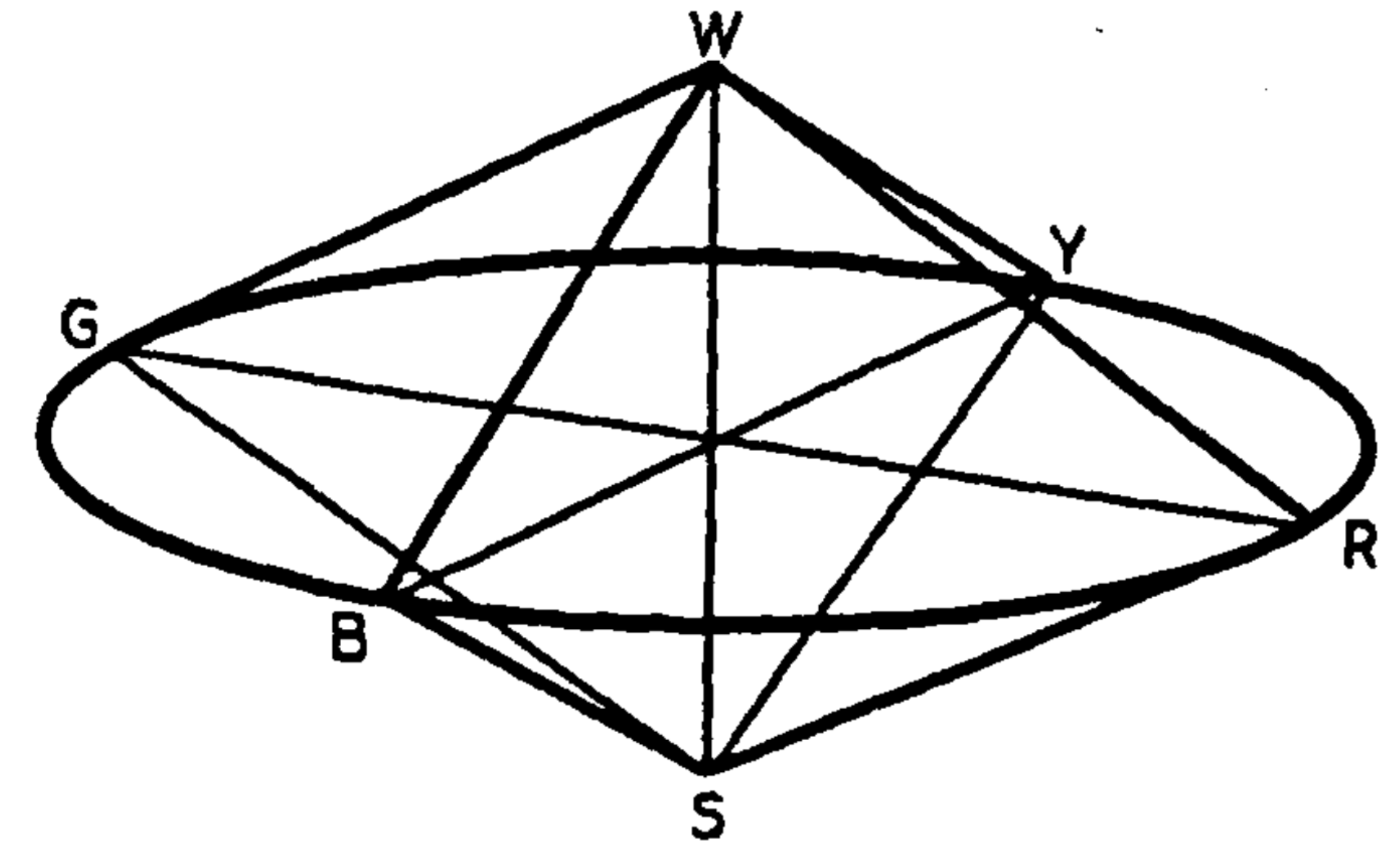

Conceptual spatial representation allows for a flexible understanding of similarities between concepts. Accordingly, cognitive processes like similarity assessment or categorization can be better explained by the proximity –or distance– between concepts in a conceptual space. For example, the color space, usually discussed as an archetype of a conceptual space, has quality dimensions such as hue, saturation, and lightness. In this space, similarly colored stimuli are closer together while differing colors are farther apart.

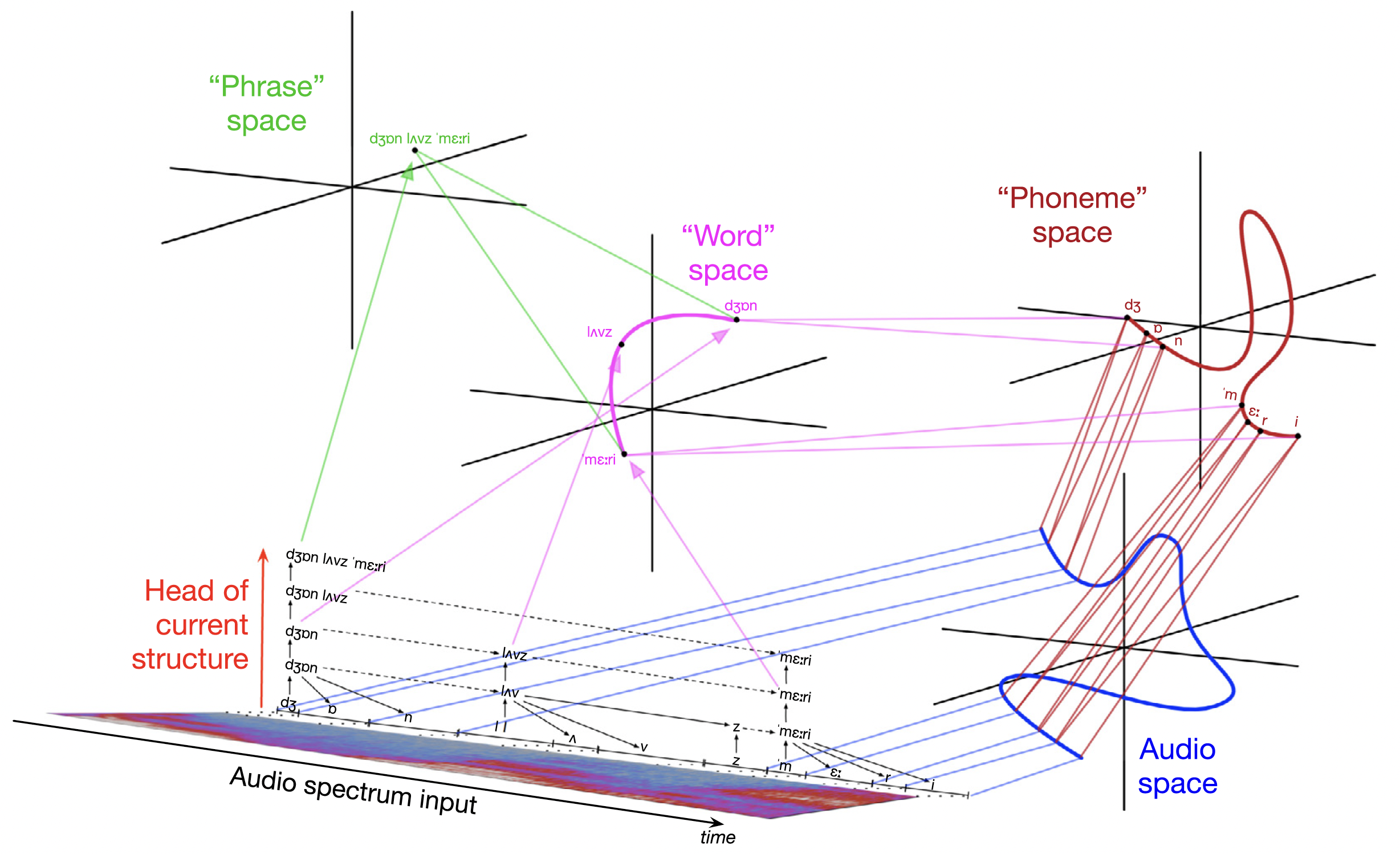

To better envision the idea of how conceptual spaces are extremely complex representations in the mind, usually involving many quality dimensions, Geraint Wiggins proposes an example of a spoken phrase and how it is mentally represented in terms of conceptual spaces (in this particular case, the representation is limited to the different time regularities existing on a sonic stimuli). The schematization of the model supposes that it has been exposed to the English language and speech and that it has learned the components of the example sentence. Still, this is an example of an idealized representation. In reality, conceptual spaces would potentially involve many more sensory dimensions as well as semantic dimensions.

From this perspective, it becomes relatively clear how the concept of conceptual spaces, along with their inherent complexity and multidimensionality, relates to creativity. However, connecting this idea back to artistic creation as a process of exploration, using the metaphor of the labyrinth as I discussed in the introduction, becomes more challenging to imagine, since any creative exploration would entail a complex network of interrelated multisensory and semantic spaces.

Margaret Boden proposes that, as models for creative processes, conceptual spaces comprise essentially structured styles of thought,* Boden, The creative mind: myths and mechanisms, 4. rather than solely multisensory experiences. These styles of thought encompass a wide range of creative expressions, including music, writing, sculpting, illustration, and countless other cultural practices –like fashion and cuisine, among others. Additionally, Boden highlights that these conceptual spaces are not just individual constructs. Rather, they draw from existing societal ideas and are shaped by our interactions with the world.

Formal systems

Margaret Boden’s model of human creativity revolves around the notion of conceptual spaces as a process of exploration of these very complex conceptual spaces.* Margaret A. Boden, "Computer Models of Creativity," Interfaces 1993, no. April (1993); Margaret A. Boden, "Creativity and artificial intelligence," Artificial Intelligence 103, no. 1-2 (1998), https://doi.org/10.1016/s0004-3702(98)00055-1; Boden, The creative mind: myths and mechanisms; Margaret A. Boden, Creativity and art: three roads to surprise (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010). But how are these spaces explored? As I mentioned in the introduction to this text and as somehow became clear after the lengthy theoretical discussion from before, there are different ways of doing it. Potentially, one related to logical steps and reason, and another one related to intuitive moves. Concerning the first, Boden proposes that explorations of these spaces are based on formal systems. Douglas Hofstadter defines a formal system as sets of rules and symbols used to create and manipulate statements or strings of symbols. Importantly, there is no need to attribute inherent meaning to these symbols; the exploration can remain agnostic to the content being explored.* Douglas R. Hofstadter, Gödel, Escher, Bach (Basic Books New York, 1979).

This approach has been a common creative and exploratory practice, especially in WACM. Particulalry illustrative of this is the example of the European post-war avant-garde movements, which developed a creative trend by applying combinatorial formulas to organize musical parameters, particularly pitch, and rhythm, though not limited to these alone. However, the concept of a formal system in music can extend beyond the combinatorial –and somewhat rudimentary– logic of some avant-garde methods. Counterpoint rules, harmonic structures, and even principles of orchestration can be understood as formal systems: chords unfold based on harmonic patterns, and melodies interact within polyphonic textures according to specific intervallic movements, both horizontally and vertically. For instance, when a musical movement “X” is allowed, it may restrict another movement “Y.” Choosing one movement constrains the following possibilities unless condition “Z” intervenes.

Some of these rules have formed a logical framework that has been the cornerstone of music composition, dating back to early polyphonic music in the Middle Ages. What may sound like a logical, computer-like method, in fact, has been an important way of exploring creative spaces in music –and I will dedicate the next chapter to better understanding this process as it unfolds within my creative practice. However, there is an important concept that needs to be introduced here, and that is the notion of heuristics.

Heuristics

Heuristics are mental shortcuts or rules of thumb that simplify decision-making or problem-solving, often providing quick but not always optimal solutions. In AI, heuristics are used to speed up algorithms by guiding them toward likely solutions, aiming to balance efficiency with accuracy in complex problem-solving tasks. Furthermore, using heuristics helps us avoid repeating or going through unneeded steps in any process. Sometimes, heuristics processes allow us to “jump” the walls of the labyrinth by breaking some rules to prioritize some desired outcomes. For example, it is common to see in some great composers how they broke some harmonic rules –such as the prohibition of moving harmonic voices in parallel 5ths or 8ves– in order to prioritize a beautiful melodic result.

At first sight, heuristic thinking, which is a capacity that is very familiar to human art practitioners, is a crucial separation between human creativity and computational algorithms. However, the idea of heuristics also exists in AI, and computers are far from being stupid logical calculators –and this has been the case for a long time! Nonetheless, composing music solely through formal systems at some point became almost prescriptive for many contemporary composers, who focused exclusively on the symbolic dimension of music. Whether this approach was –or is– valid or not is an issue that spills into broader philosophical, ideological, historical, technical, and ultimately aesthetic discussions. However, it is a question that I will explore further in the following chapter, ‘The Cognitivist Paradigm.’ Computers, especially with the advent of AI, have proven to be powerful tools in this area. So, let me now shift attention from human cognition to AI and examine relevant concepts in this field.