The Connectionist Approach

Oscillations

The work Oscillations is a cycle of three pieces inspired by the lieder cycle Winterreise, written by W. Müller and set to music by F. Schubert. Winterreise explores themes of isolation, loneliness, existential questioning, and the search for purpose amid despair. I believe these themes remain profoundly relevant in today’s society. In the following discussion, I will examine some relevant aspects of this work, and later, I will trace some connections between these and the creative process for Oscillations.

Schubert-Müller’s Winterreise* Schubert and Müller's Winterreise has been extensively discussed in numerous books, articles, and academic dissertations. Particularly relevant to me are Susan Youens, Retracing a winter's journey : Schubert's Winterreise (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1991), Kindle ed., and the collection of essays The Cambridge Companion to Schubert's ‘Winterreise', ed. Marjorie W. Hirsch and Lisa Feurzeig, Cambridge Companions to Music, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021).

Winterreise (German, Winter trip in English), is probably one of Schubert’s most profound compositions. It has been described as “inspired by the poetry of Müller and its poeticized philosophy of existential torment”.* Susan Youens, Retracing a winter's journey: Schubert's Winterreise The protagonist of the story is a young wanderer who embarks on a solitary journey after being abandoned by his beloved. However, Müller extends this theme beyond mere grief over a sweetheart’s infidelity, raising fundamental questions about the meaning of existence. As he travels, the wanderer seeks to understand both his own nature and that of Humanity through observing the external world as a fleeting landscape and through introspection and inward exploration.* In this context, the idea of inward exploration refers to the search for deeper meaning or truth within oneself. The Weg nach Innen (German for path inward) is a concept from German Romanticism, particularly associated with the poet and philosopher Novalis (Friedrich von Hardenberg) and found in his unfinished novel Heinrich von Ofterdingen. Müller was familiar with Novalis’ work.

Throughout the cycle, the wanderer speaks to himself as if entirely alone, drawing the reader directly into his thoughts with no narrator or intermediary. According to Susan Youens, the reader appears as an eavesdropper, listening to things never meant to be overheard. In this sense, Winterreise is a monodrama and a precursor to Expressionist interior monologues.* A monodrama is a theatrical or musical work performed by a single actor or singer. It typically involves intense psychological depth and focuses on the inner world of the protagonist. Examples of monodramas are the works Erwartung (1909) by Marie Pappenheim and Arnold Schoenberg, and Schoenberg’s Die Glückliche Hand (1913). Furthermore, Müller deliberately adopts the style of German folk poetry* Wilhelm Muller was a German poet and writer who is known for his contributions to the development of the German Volkslied, or folk song. See for example Philip S. Allen, "Wilhelm Muller and the German Volkslied," Journal of Germanic Philology, 3 (1900). in Winterreise to create a monodramatic effect. By avoiding complex poetic structures and the presence of multiple voices –such as a narrator or the poet himself– the poetry feels more direct and emotionally immediate.

Susan Youens proposes that Müller was fond of antitheses, and this is reflected in the poetic style of Winterreise: as the wanderer walks, he shifts between self-reflection and outward observations of nature and mankind, while his psyche oscillates like a pendulum between euphoria and a longing for death, reality and imagination, and past and present. An example of this is the antithetical phrase “A stranger I arrived, / A stranger I depart” at the beginning of the first poem, “Gute Nacht,” which characterizes much of the cycle’s lyricism. These antithetic states and sensations appear throughout the entire cycle.

The wanderer experiences deep feelings throughout the cycle, yet Youens suggests he is also a realist with an analytical and philosophical mind. He sees his misery clearly and finds no comfort in dreams or fantasies because he doesn’t believe they have any connection to real life. To him, the divide between them is absolute. Returning to solitude and isolation after a brief escape into dreams is a recurring theme throughout the twenty-four songs. Youens provides an example of this in the poem “Frühlingstraum,” where the fleeting dream of green meadows and reciprocated love is followed by a sudden and acute awareness of cold and loneliness upon awakening.

Frühlingstraum

Wilhelm Müller

Ich träumte von bunten Blumen,

So wie sie wohl blühen im Mai,

Ich träumte von grünen Wiesen,

Von lustigem Vogelgeschrei.

Und als die Hähne krähten,

Da ward mein Auge wach;

Da war es kalt und finster,

Es schrieen die Raben vom Dach.

Doch an den Fensterscheiben

Wer malte die Blätter da?

Ihr lacht wohl über den Träumer,

Der Blumen im Winter sah?

Ich träumte von Lieb’ um Liebe,

Von einer schönen Maid,

Von Herzen und von Küssen,

Von Wonne und Seligkeit.

Und als die Hähne krähten,

Da ward mein Herze wach;

Nun sitz’ ich hier alleine

Und denke dem Traume nach.

Die Augen schliess’ ich wieder,

Noch schlägt das Herz so warm.

Wann grünt ihr Blätter am Fenster?

Wann halt’ ich mein Liebchen im Arm?

Dream of Spring

Translated with DeepL.com (free version)

I dreamed of colorful flowers,

The way they bloom in May,

I dreamed of green meadows,

Of merry birdsong.

And when the roosters crowed,

My eyes woke up;

It was cold and dark,

The ravens cried from the roof.

But on the window panes

Who painted the leaves there?

You must be laughing at the dreamer,

Who saw flowers in winter?

I dreamed of love for love,

Of a beautiful maiden,

Of hearts and kisses,

Of delight and bliss.

And when the roosters crowed,

My heart awoke;

Now I sit here alone

And think about the dream.

I close my eyes again,

My heart still beats so warmly.

When will her leaves turn green at the window?

When will I hold my love in my arms?

A recurring theme throughout the cycle, as discussed by Youens, is the difficulty of dying when one longs for it, or the persistence of life, even when unwanted. Yet the wanderer considers something like suicide only once, and even then, not by his own hand but as a passive surrender to nature. This moment, in the fifth song, “Der Lindembaum” (German, Linden tree in English),* In German literature, the linden tree often symbolizes home, comfort, and memory. It appears frequently in folk songs and poetry as a place of shelter, love, or longing. See for example Uwe Hentschel, "Der Lindenbaum in der deutschen Literatur des 18. und 19. Jahrhunderts," Orbis litterarum 60, no. 5 (2005), https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0730.2005.00843.x. is a key turning point. Until now, he has remained in the town of his beloved, and when he finally begins his journey, he is nearly stopped by the temptation to stay, lost in memory, and let the winter storm take him. Even though he doesn’t know why, he still holds to a trace of hope and chooses to keep moving.

Der Lindenbaum

Wilhelm Müller

Am Brunnen vor dem Tore,

Da steht ein Lindenbaum;

Ich träumt’ in seinem Schatten

So manchen süssen Traum.

Ich schnitt in seine

Rinde So manches liebe Wort;

Es zog in Freud’ und Leide

Zu ihm mich immer fort.

Ich musst’ auch heute wandern

Vorbei in tiefer Nacht,

Da hab’ ich noch im Dunkel

Die Augen zugemacht.

Und seine Zweige rauschten,

Als riefen sie mir zu:

Komm her zu mir, Geselle,

Hier findst du deine Ruh’!

Die kalten Winde bliesen

Mir grad’ in’s Angesicht,

Der Hut flog mir vom Kopfe,

Ich wendete mich nicht.

Nun bin ich manche

Stunde Entfernt von jenem Ort,

Und immer hör’ ich’s rauschen:

Du fändest Ruhe dort!

The Linden Tree

Translated with DeepL.com (free version)

At the fountain outside the gate,

There stands a linden tree;

I dreamed in its shade

Many a sweet dream.

I cut into its bark

Many a sweet word;

It drew me in joy and sorrow

I was always drawn away to him.

I had to wander today too

Past in the deep night,

Still in the dark

I closed my eyes.

And its branches rustled,

As if they were calling to me:

Come to me, fellow,

Here you'll find your rest!

The cold winds blew

Straight into my face,

My hat flew off my head,

I did not turn.

Now I am many an hour

Away from that place,

And I can always hear it rustling:

You would find rest there!

Even as the linden tree’s voice, whispering of rest and peace in death, continues to haunt him, the poetry of Winterreise remains strikingly realistic. There are no fairy-tale or supernatural elements in the text. Instead, any seemingly “magical” moments –like the voices calling “Come here to me, fellow” in “Der Lindembaum”– originate from the wanderer’s own mind, and he is fully aware of it.

In the final song, “Der Leiermann,” the wanderer encounters a solitary beggar playing a hurdy-gurdy. Youens interprets this old man as the wanderer’s doppelgänger,* In German literature, the Doppelgänger represents a double or shadow self, often symbolizing inner conflict, fate, or an inescapable aspect of one’s identity. It appears in works by authors like E.T.A. Hoffmann and Heinrich Heine, frequently as a augury of doom or existential crisis. See for exampleAndrew J. Webber, Andrew J. Webber, The Doppelgänger: Double Visions in German Literature (Oxford University Press, 03 Oct 2011, 1996). https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198159049.001.0001. a reflection of what he is becoming, embodying his deepest fears of the future. In the end of his trip, reality forces him to accept that his beloved is lost, and to survive, he must sever his ties to the past.

Der Leiermann

Wilhelm Mueller

Drüben hinter’m Dorfe

Steht ein Leiermann,

Und mit starren Fingern

Dreht er was er kann.

Barfuss auf dem Eise

Schwankt er hin und her;

Und sein kleiner Teller

Bleibt ihm immer leer.

Keiner mag ihn hören,

Keiner sieht ihn an;

Und die Hunde knurren

Um den alten Mann.

Und er lässt es gehen

Alles, wie es will,

Dreht, und seine Leier

Steht ihm nimmer still.

Wunderlicher Alter,

Soll ich mit dir geh'n?

Willst zu meinen Liedern

Deine Leier dreh'n?

The Hurdy-Gurdy Player

English translation by Richard Wigmore* I use the English translation of the poem by Richard Wigmore, author of Franz Schubert and Richard Wigmore, The complete song texts: texts of the lieder and Italian songs (New York: Schirmer Books, 1988), provided via Oxford International Song Festival (www.oxfordsong.org).

There, beyond the village,

stands a hurdy-gurdy player;

with numb fingers

he plays as best he can.

Barefoot on the ice

he totters to and fro,

and his little plate

remains forever empty.

No one wants to listen,

no one looks at him,

and the dogs growl

around the old man.

And he lets everything go on

as it will;

he plays, and his hurdy-gurdy

never stops.

Strange old man,

shall I go with you?

Will you turn your hurdy-gurdy

to my songs?

According to Youens, Winterreise is usually interpreted as culminating in death or madness. However, despite the bleak emotional progression, the language of the wanderer remains consistent throughout the cycle. The landscape at the end –an unnamed town, a pack of dogs, snow, and ice, appears to return to the beginning of the journey, suggesting that the Winterreise has come full circle.

Ekphrasis and Misreading

The work Oscillations proposes a re-imagination and re-composition of some songs of Winterreise through a personal vision and compositional approach. The work investigates several artistic inquiries. Some of them, as I see it, are at the intersection between human and artificial creative cognition: On the one hand, some musical and literary content of the cycle becomes prompt for a neural generative system. On the other hand, evocations and recollections are re-imagined as a new narrative for the poetry, a process that I view in analogy to prompt, but using a human mind as a latent space. Additionally, some musical references and poetic symbols from Winterreise are reimagined and incorporated as sources for re-composing them into a new musical work.

My main personal and artistic motivation for composing this piece is strongly related to the current relevance of the topics that Müller and Schubert immortalized in their Winterreise. In addition to that, the deeply poetic and musical treatment of these issues in the cyclic has always strongly resonated with me. But how do I say what Schubert and Müller said in the past, with my own words? Somehow, I feel a need to misread it, not only in a literary sense but also musically.*The idea of 'misreading' as a creative practice in 20th-century music comes originally from J. Straus, who also took it from Harold Bloom. See Joseph N. Straus, "The 'Anxiety of Influence' in Twentieth-Century Music," The Journal of Musicology 9, no. 4 (1991), https://doi.org/10.2307/763870.

There is a relatively common trend among some composers that write pieces that are responses to preexisting compositions, in particular Schubert’s works. For instance, Dániel Péter Biró’s To Remember and Forget (1999-2000),* A detailed analysis of To Remember and to Forget can be found in D. Biró, "Remembering and Forgetting: Lizkor VeLishkoach for String Quartet, after Schubert." a response piece to Schubert’s Quartet in G major (D887). Similarly, Hans Zender’s Winterreise (1993) is a reinterpretation of Schubert-Müller’s Winterreise, and Henrik Hellstenius’s Dichterliebe (2015), a re-composition of the Schumann-Heine cycle, among many others. Some theorists have described this approach as ekphrastic. In this way, there is something ekphrastic in Oscillations, as each piece is an original work inspired by and connected to the cycle Winterreise.

Ekphrasis, in its classical form, is primarily a discoursive technique that aims to vividly represent absent objects or scenes for an audience, making the listener feel like an eyewitness.* Ruth Webb, Ekphrasis, imagination and persuasion in ancient rhetorical theory and practice (Abingdon, UK: Taylor & Francis Group, 2013), 1. However, in modern interpretations, the use of ekphrasis has shifted towards a focus on the explicit representation of visual artworks.* James A. W. Heffernan, "Ekphrasis and Representation", New Literary History 22, no. 2 (1991), https://doi.org/10.2307/469040 Furthermore, contemporary ekphrasis extends beyond just visual art, touching on other art forms like music. This idea shifts ekphrasis from a mere descriptive practice to a dynamic interplay between multiple artistic mediums. These can either reflect direct influences from other artistic works or re-imagine them in a practice that potentially brings new dimensions and interpretations: a form of creative re-presentation.* Lydia Goehr, "How to Do More with Words. Two Views of (Musical) Ekphrasis," British Journal of Aesthetics 50, no. 4 (2010), https://doi.org/10.1093/aesthj/ayq036

The composer Luciano Berio, for example, wrote a piece named Ekphrasis (Continuo II) in 1996. As its name indicates, the work functions as a commentary on an earlier composition of his: the 1990 orchestral piece called Continuo. There is another piece by Luciano Berio, however, that interests me more, as it also takes as a departure point the music of Franz Schubert: The piece Rendering (1990) for symphonic orchestra. According to his own words, Berio composed this piece in the form of a restoration of Schubert’s Tenth Symphony in D major (D936A):

“Seduced by those sketches, I therefore decided to restore them: restore and not complete nor reconstruct. […] I proposed to follow, in spirit, those modern criteria of restoration that address the problem of rekindling the old colors without hiding the damage of time and the inevitable gaps created in the composition (as is the case with Giotto in Assisi).”

Schubert’s symphony sketches were left in pianistic form, with occasional instrumental suggestions. Berio’s restoration focused on completing the internal voices and bass lines, along with orchestrating the piece, aiming to preserve Schubert’s characteristic color, though not exclusively, as Berio refers to using orchestration techniques resembling Mendelsohn and Mahler in Rendering.

To bridge the gaps between sketches, Berio gradually introduces new musical material that slowly emerges, first coexisting with Schubert and later taking over the orchestral texture. This connecting tissue –as he defines it– is constantly different and changing, always pianissimo and lontano. Even though the new material feels entirely distinct from Schubert’s, Berio manages to knit them in an undeniably beautiful and masterfully conceived form.

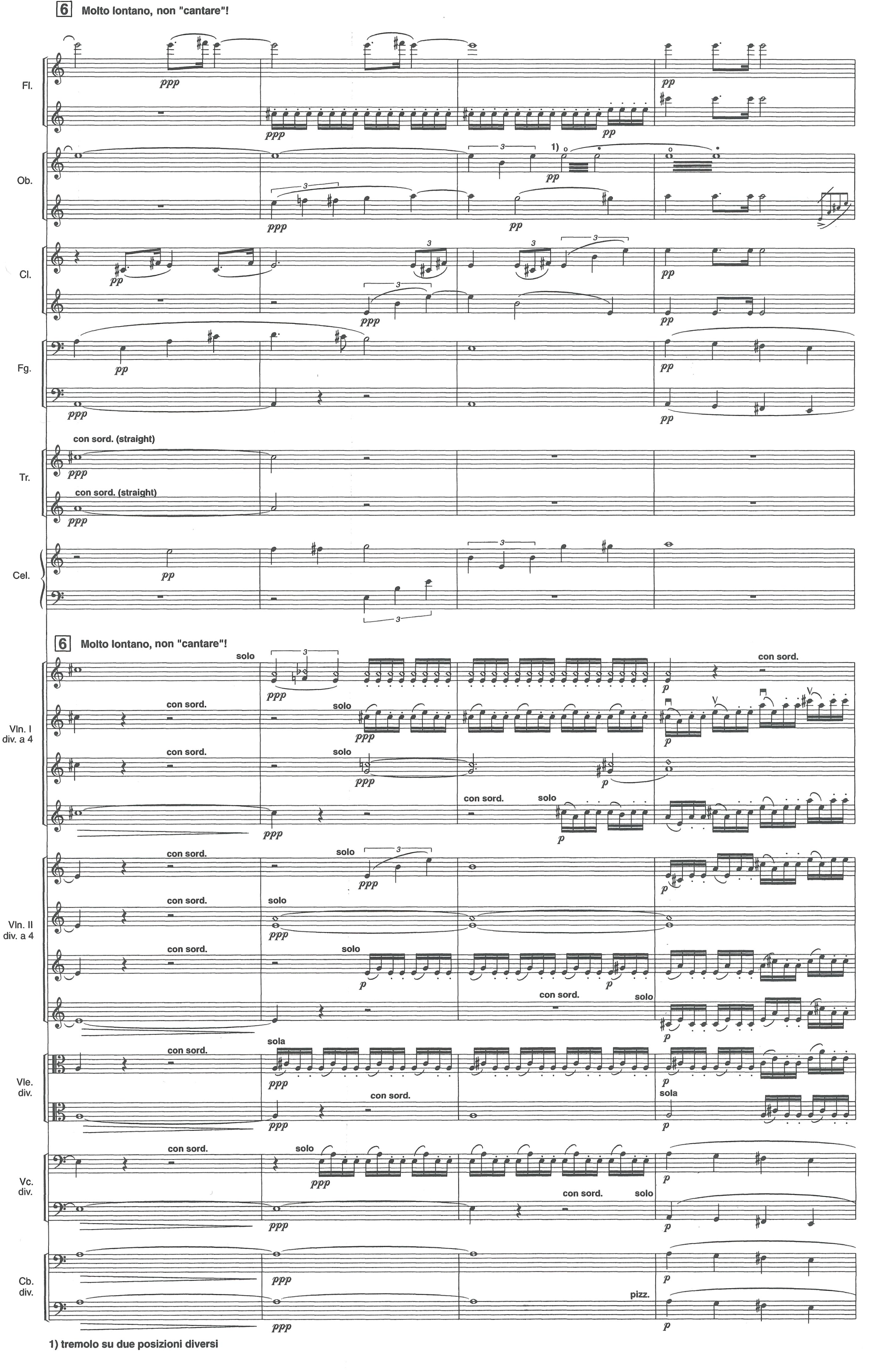

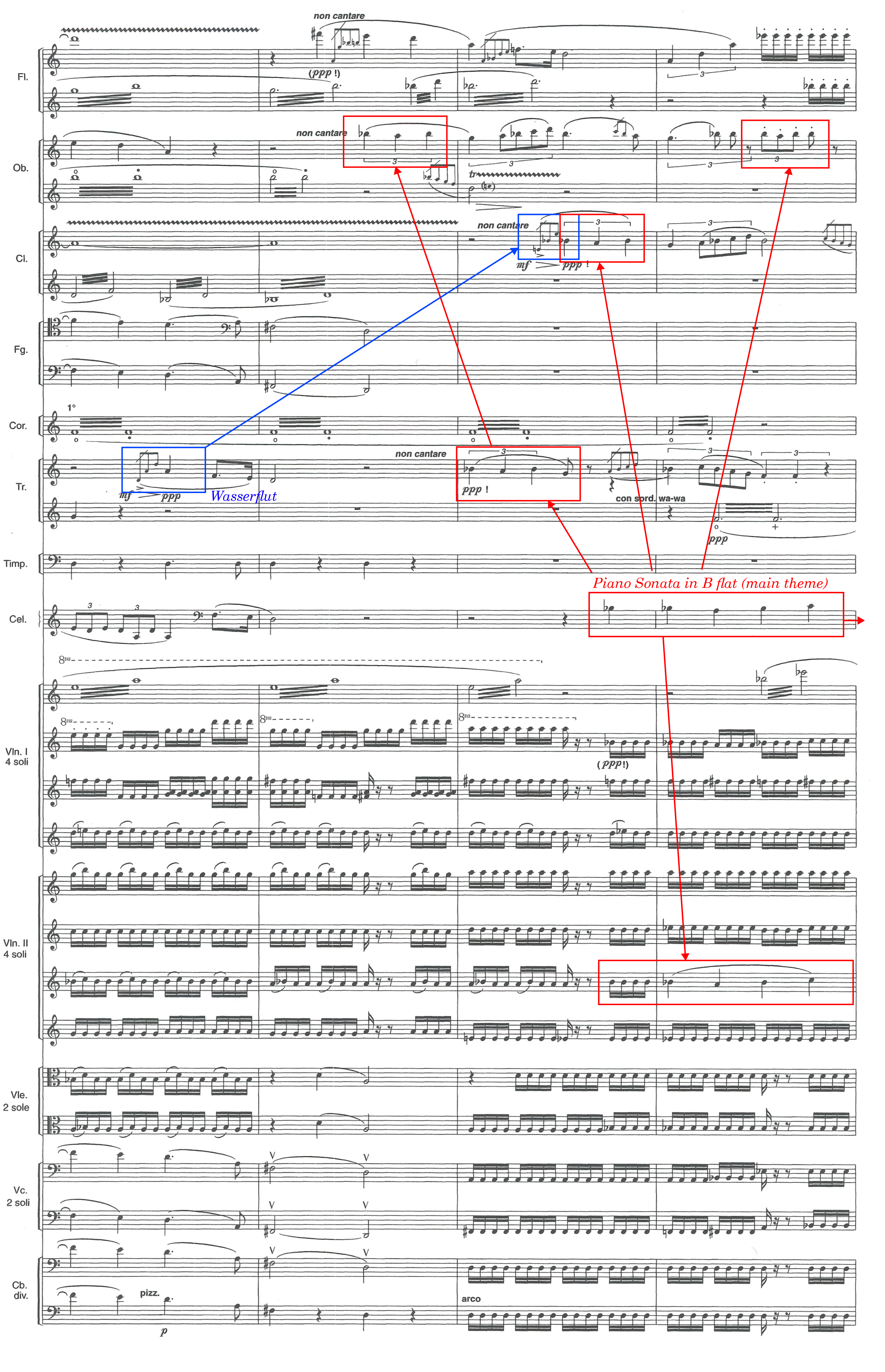

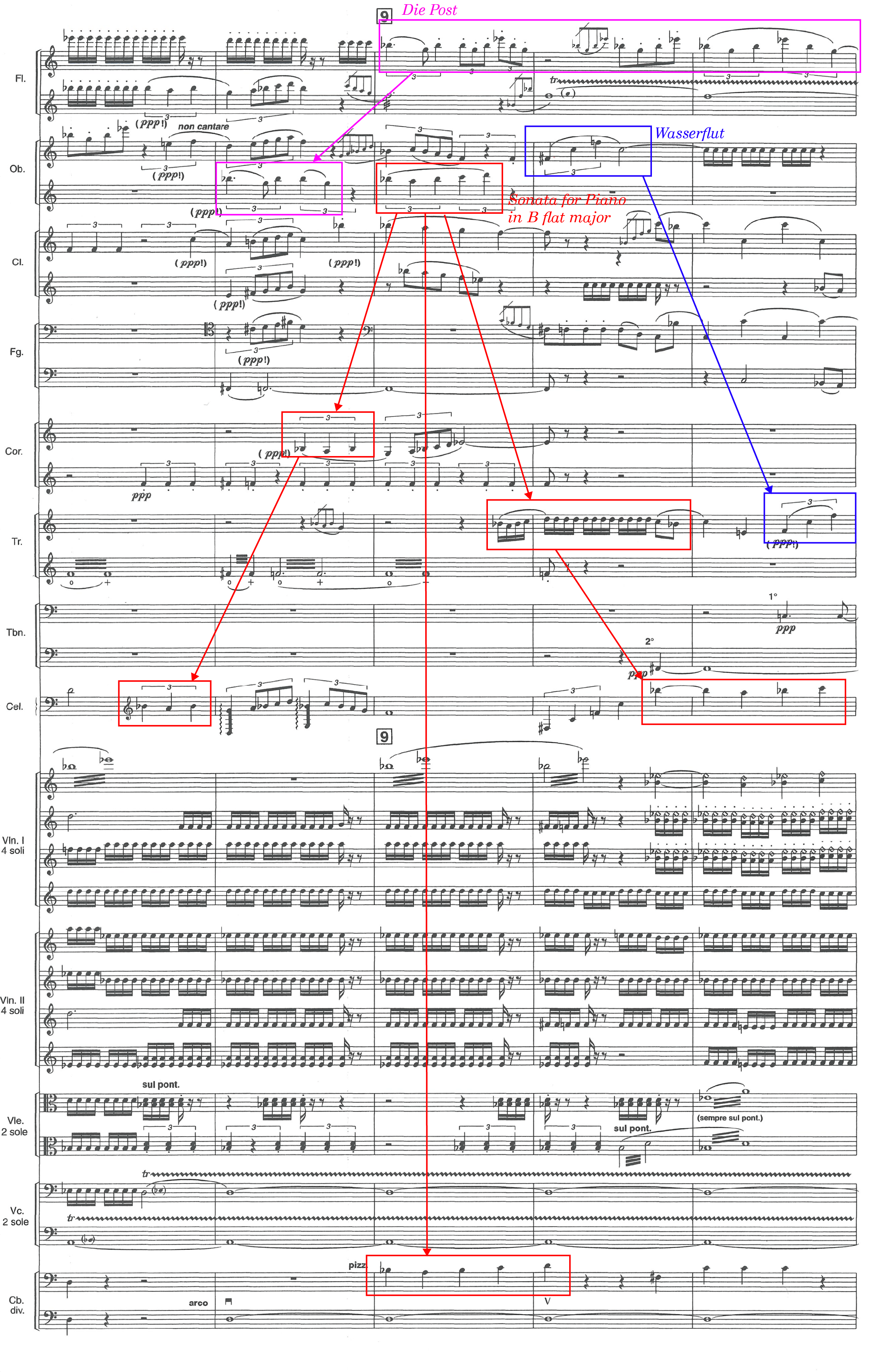

Some of these interjections of the connecting tissue intertwine fragments of late Schubert works, such as the Piano Sonata in B flat major (D960), the Piano Trio in B flat major (D898), as well as some songs of Winterreise.* A lengthy analysis of Renderings including a longer description around Schubert’s original material and its transformation can be found in Thomas Gartmann, ""... dass nichts an sich jemals vollendet ist" : Untersuchungen zum Instrumentalschaffen von Luciano Berio," Publikationen der Schweizerischen Musikforschenden Gesellschaft. Serie 2 37 (1995), https://doi.org/10.5169/seals-858818 For example, the fragment below shows some abbreviated quotations of the main theme from the Piano Sonata in B-flat major. The first oboe, trumpet and clarinet play the first three notes before diverging. Soon after, the first oboe diminishes the rhythm. The violins play the motive as repeated sixteen-notes. Finally, the celesta presents the first phrase of the theme in its literal melodic form, without harmony, doubled by the second violins.

In Rendering, some references to Winterreise can be observed. For instance, the beginning of “Wasserflut” (the sixth song of the cycle), characterized by its intervals (ascending perfect fifth, ascending and descending perfect fourth), is rhythmically condensed here into a succession of three appoggiaturas followed by a long note, as it can be seen in the score above, in the first trumpet and first clarinet (here the quotation to “Wasserflut” overlaps with a quotation to the Piano Sonata in B flat major). Later, the first oboe and first trumpet play an rhythmically augmented version of the same motive. Additionally, there is a reference to “Die Post” (the thirteenth song) in the first flute at rehearsal mark 9, featuring its characteristic broken chord and triplet rhythmic feel, as shown below:

In this piece, Berio seems to invert the concept of historical material as exemplified earlier in Bernd Zimmermann’s work. Rather than allowing historical elements to emerge organically within a contemporary framework, Rendering introduces the contemporary only sparingly, serving as a subtle connective tissue that binds together Schubert’s fragmented sketches. The collision of the historical material with the new, the dreamy texture and their intertwining shocked me greatly at first listening and every time after.

Creative Process

The cycle Oscillations is inspired by, and both musically and poetically rooted in the music and poetry of Winterreise. In particular, Müller’s poetic concept of antithesis, discussed above, is reinterpreted as a central creative idea for the piece: the notion of oscillating musical states, in relation to themes of deviation, drifting, and return.

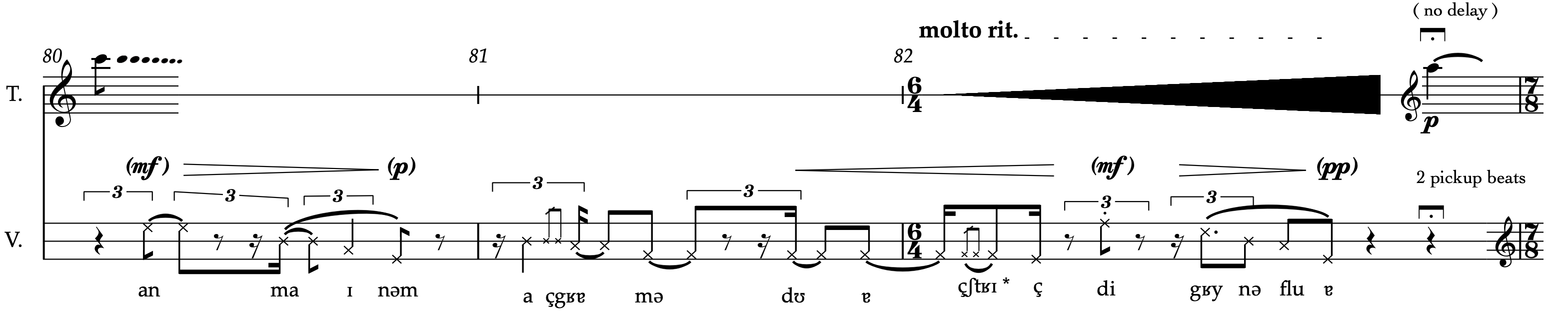

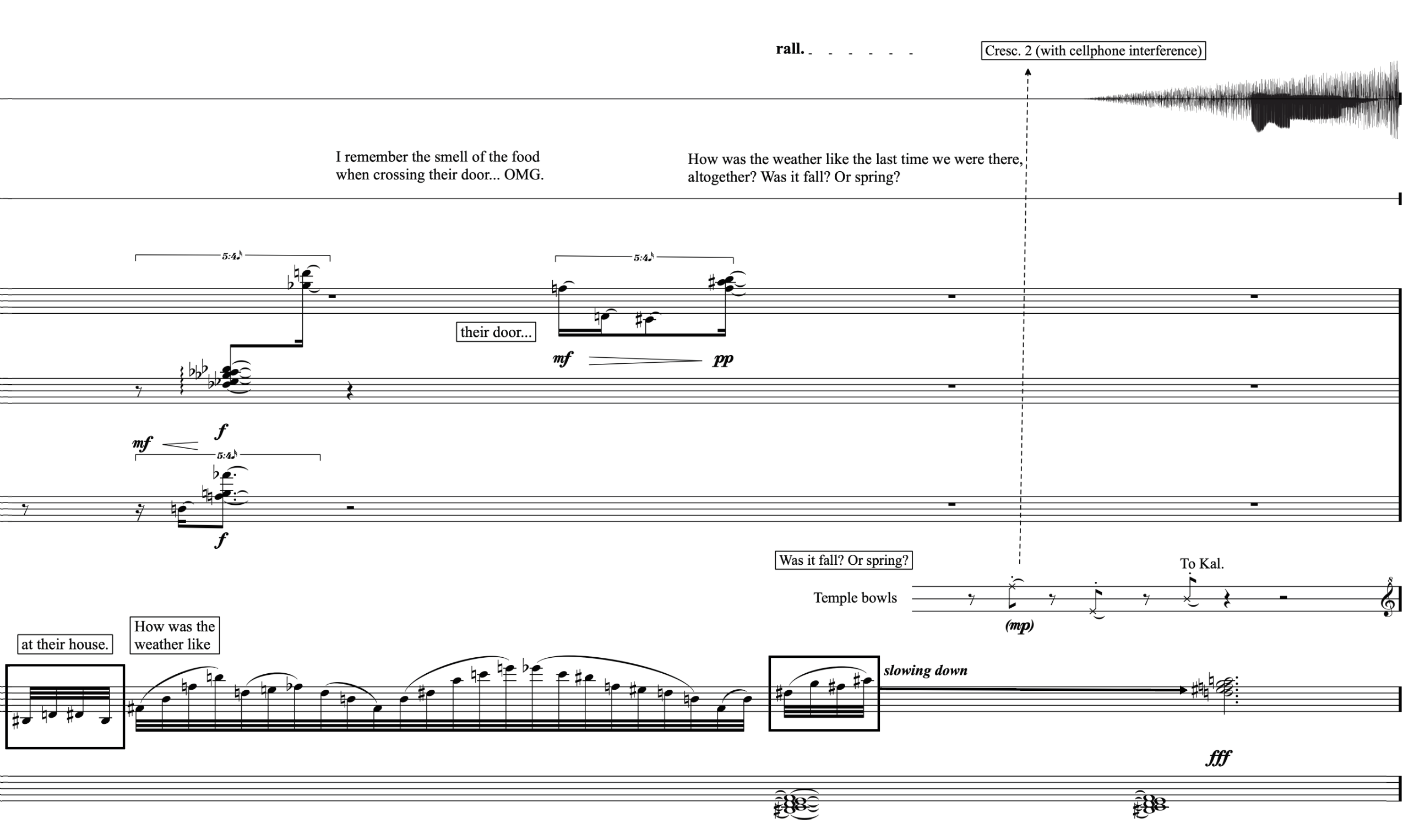

The nature of these oscillations and how it is creatively explored varies across the three pieces. Oscillations (i) essentially draws material from the poems “Gute Nacht,” “Gefrorene Tränen,” and “Erstarrung.” Oscillations (ii) uses “Der Lindembaum” as its starting point –also incorporating a covered quotation of the piano part from “Gute Nacht.” Oscillations (iii) takes inspiration and material from “Der Leiermann” and includes a covered quotation of the poetry of “Mut!” After exploring more abstract constructive processes in Oscillations (i), the work gradually evolves into a form of melodrama,* The difference between monodrama and melodrama is that a melodrama usually consists of narrated voice instead of a sung part. imaginatively connected to a strongly emotional personal history through the use of sonic memories, literary narratives, and staging.

An example of the opposite process is Oscillations (ii). There, quotations from the original drive the narrative, and these materials become characters that interact with other new elements, perhaps clashing or establishing a co-existence but essentially fading into each other or emerging. Somehow, connected to Berio’s idea in Rendering. Finally, in Oscillations (iii), the historical materials shift away from their original form and then return to it, a process that repeats back and forth throughout the sections. Additionally, the narrated part mirrors this transformation through a mental drifting, using the original verses of the poem –translated into English– as its point of departure.

Neural generation and drifting

What is intuition? Intuition is the formation of connections: relationships built in the mind. Events that co-occur in space or time become connected, as P. Gärdenfor proposed; experiences that share meaning or similarity are mentally associated. Memories connect with objects: photos evoke sounds, sounds bring voices, voices recall faces, faces stir emotions, emotions summon words, and words awaken memories.

Part of the creative investigation in this piece explores intuition –both human and artificial– and the intuitive connections that can shape narrative and larger musical forms. One example of this is how I use the notion of prompt:* Prompt here is understood in the same sense as in LLMs, which refers to an initial input that guides the model’s response. In this context, this word is relevant because I am generating musical continuations; however, the terminology varies in machine learning, where we would typically refer to it as an input that determines a predictive model’s output. on the one hand, as an initializer of a generative musical process; on the other hand, as a catalyzer for a narrated part based on personal recollections, mixed with an imagined present reality. I use these two ideas metaphorically and analogously, equating them to the exploration of a latent space within a human mind –my own.

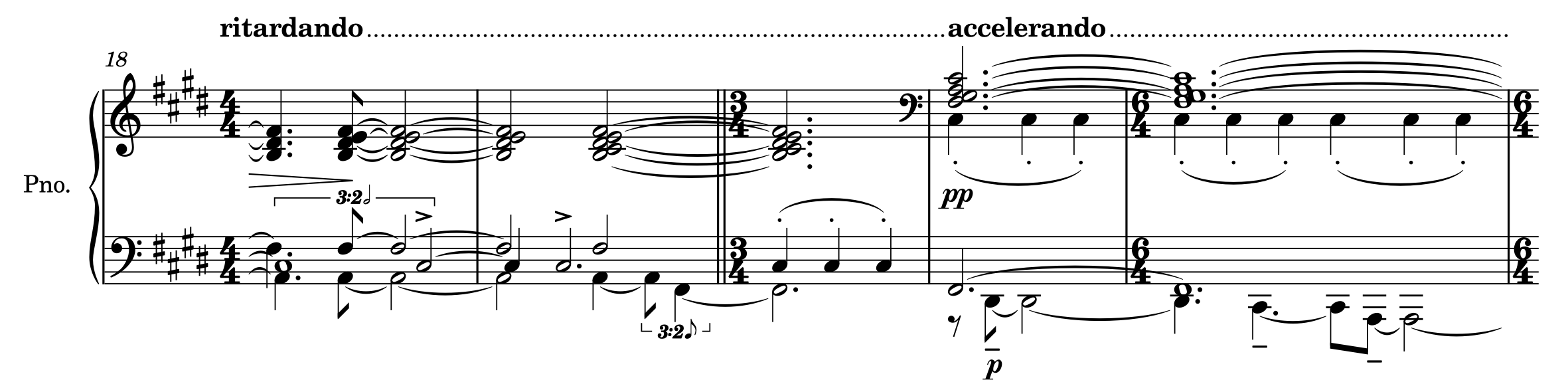

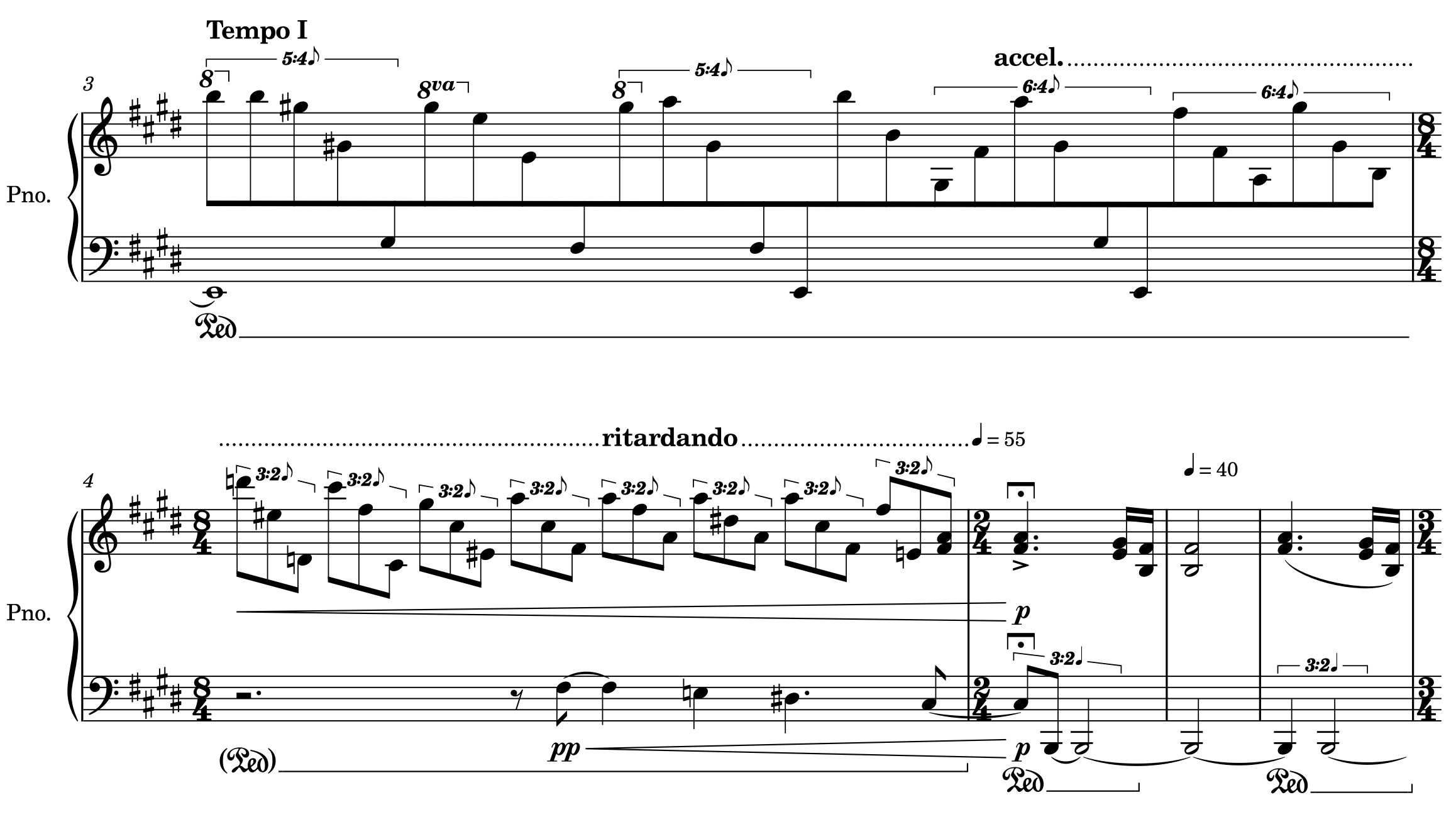

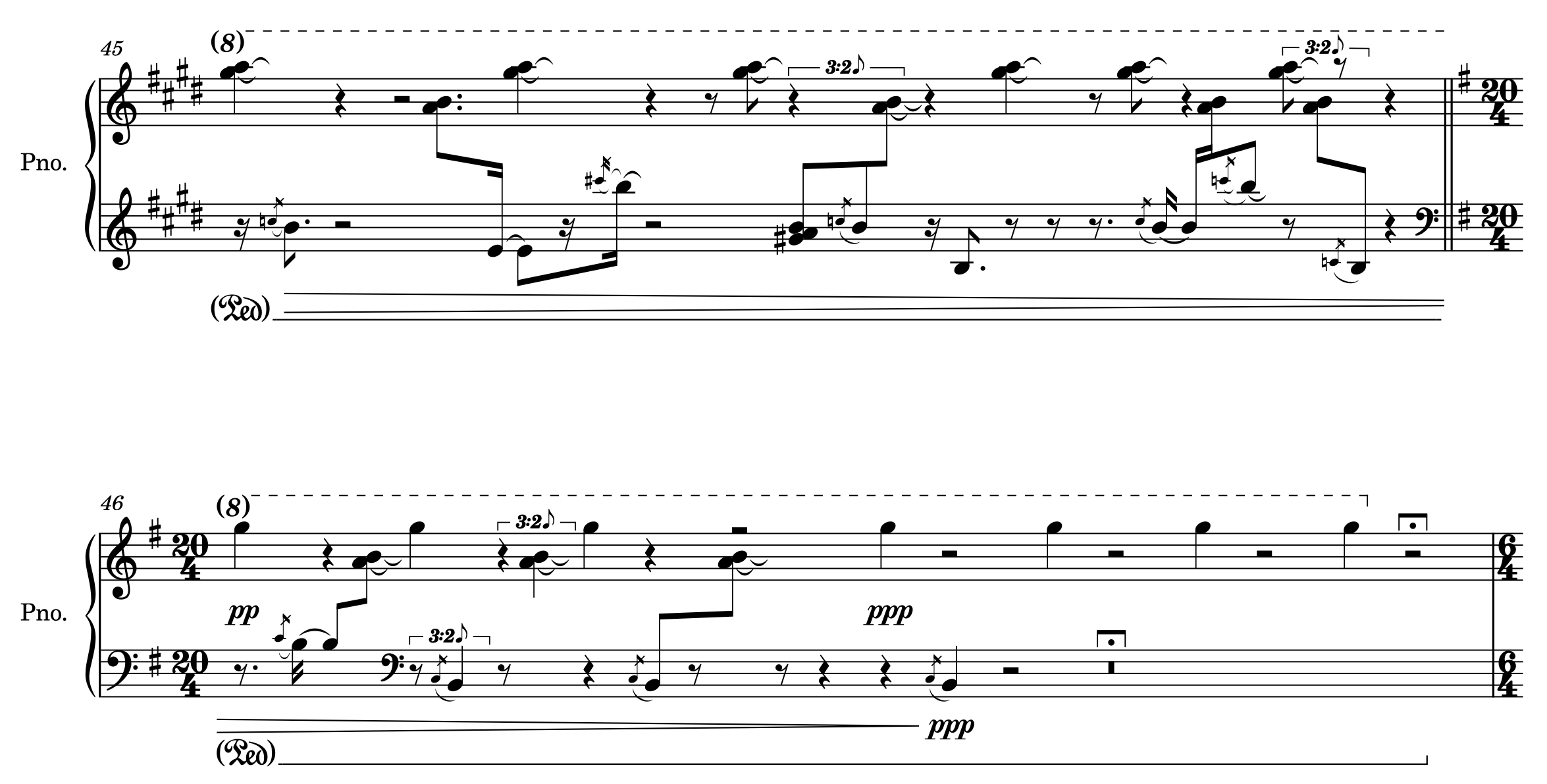

For the first idea, in this work, I experimented using the tool NeuralConstraints, which allows the generation of musical sequences guided by neural network predictions while constrained by additional rules defined by the composer. For example, the neural network can be trained on the music of the cycle Winterreise, and its outcome will be shaped by this learned data, while other rules such as allowed notes, intervals, or rhythmic repetitions shape these predictions into desired musical structures.

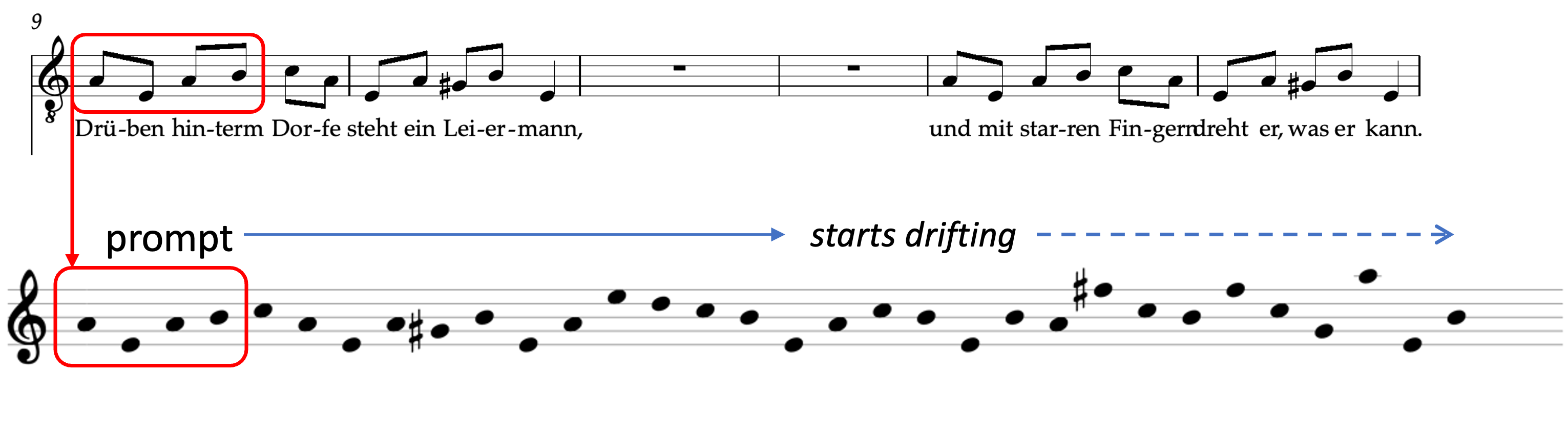

NeuralConstraints mainly works based on predictions for some input sequences. To generate a musical continuation, it usually starts from a musical prompt. For example, it receives four, or five, or whatever number of consecutive pitches, and it will try to predict the continuation. This is done sequentially step by step: the predicted outcome becomes the input for a new prediction. Therefore, these continuations can go for as long as desired. Naturally, these predictions are not always precise, and some deviations occur. Eventually, these errors start to accumulate and slowly drift away from the expected result.

This gradual deviation became a strong compositional heuristic throughout the whole work. In particular, when it takes as a departure point some literal elements of the cycle, such as some vocal melodies or piano parts. It is possible, for example, to steer the neural generation and deviation by embedding certain rules for the network to follow, or one can establish a set of rules that allow predictions to wander off while eventually returning to a targeted outcome, such as a melodic progression leading to a cadence. In the examples below, this is done through neural generation using NeuralConstraints. Later, I will discuss other examples where the “deviation” heuristic was implemented outside the computational system:

Conversely, it is possible to reverse this process, starting from random notes and slowly transforming into the original melody as a point of destination.

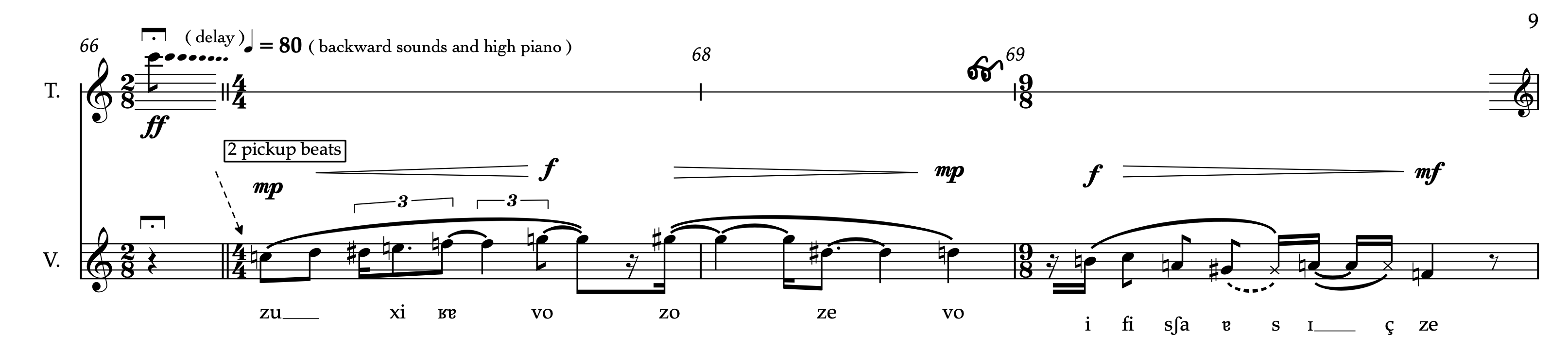

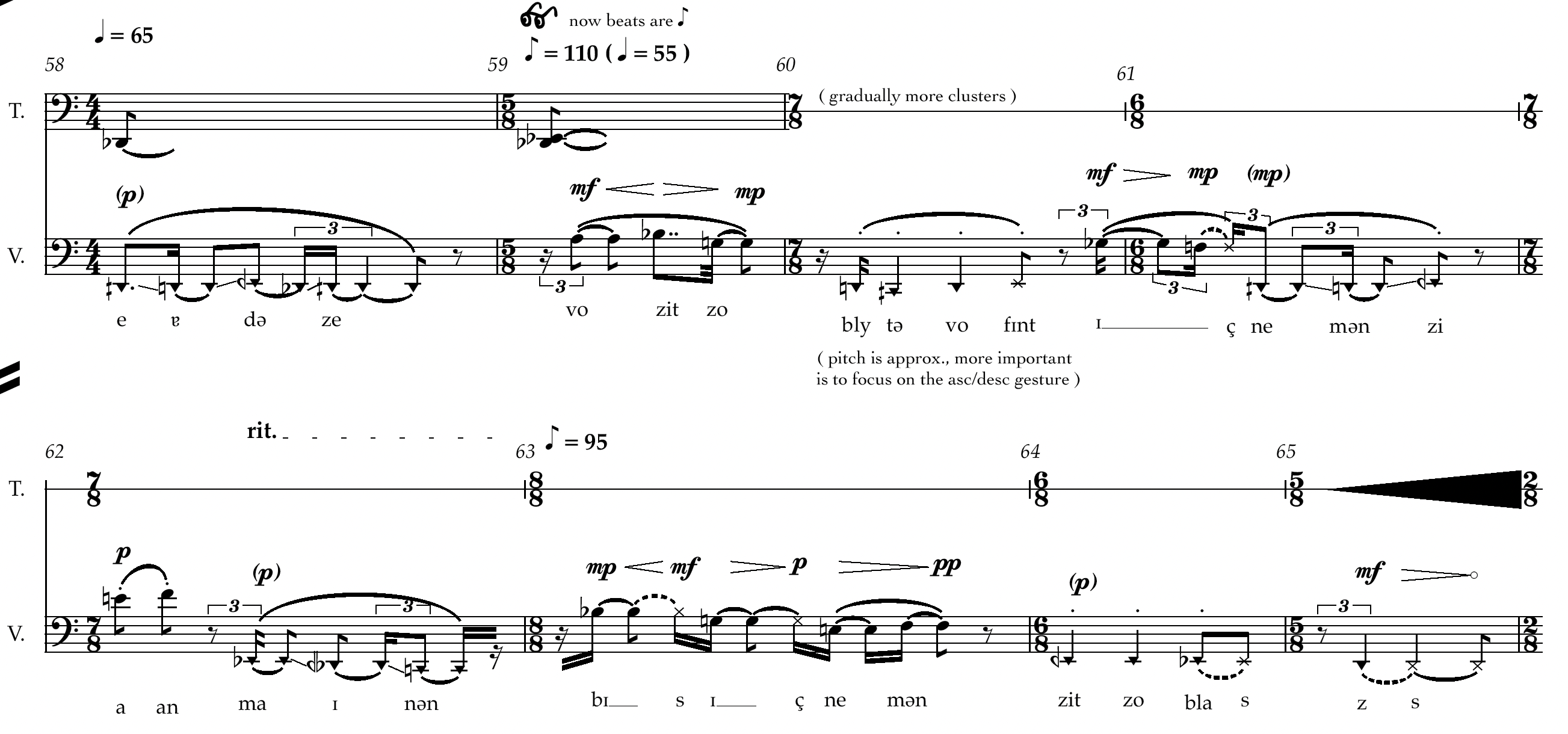

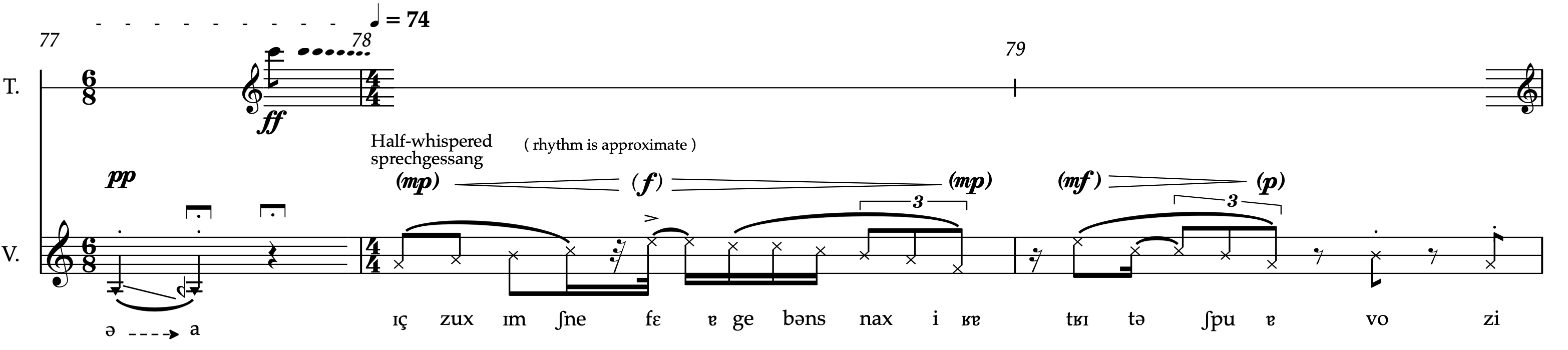

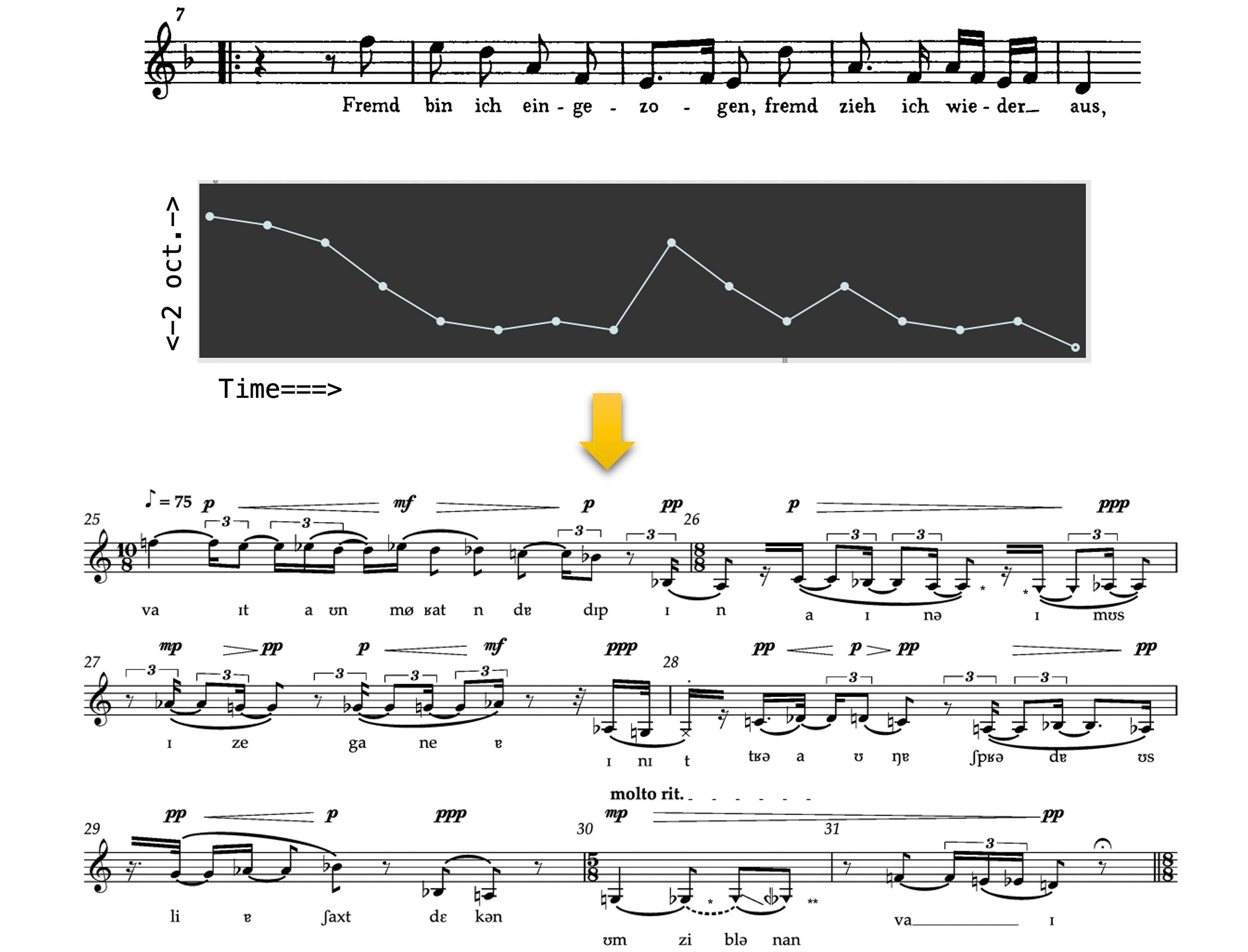

Prompting semantic connections

The narrated part of Oscillations (iii) was conceived to reflect the melodramatic essence found in Müller’s poetic style throughout Winterreise. Here, the narrator speaks to himself, in a manner not meant to be overheard. As in the original cycle, the audience is positioned as a silent observer within the narrator’s mind. The language is overtly colloquial and politically incorrect.

At the same time, this narrated part reframes the idea of prompting –somewhat connected to its musical use explained above, but this time as a metaphor for a mental drift triggered by the verses of the poem “Der Leiermann.” In this sense, this type of oscillating mental state –which is commonplace along the full cycle– here has been used not just as a compositional resource, but also as a literary mode: the original verses appear at the beginning and at the end of the narration, pronounced with a poetic narrative voice. Subsequently and over the three sections of the piece, a slow process of drifting takes place. Initially, the tone becomes totally intimate and personal, and the narrative shifts in time and space through memory evocations, yet some of the verses still evoke the original verses of the original poem. In the image below can be observed the narrated part and how it relates to “Der Leiermann.” The bold italics are indications of character for the narrator.

Electronics

The electronics in the piece are mainly based on sound samples, as well as some live processing of the instruments of the ensemble. A significant component also includes the use of soundscapes. These sonic references to objects and environments are intended to evoke some associations in the listener, connecting the sounds to emotional abstractions, specific times, or places. For instance, in Oscillations (i), a soundscape of wind and footsteps in the snow evokes a clear reference to the original Winterreise. This not only ties to the poetry but also creates a symbolic musical connection to Franz Schubert’s music, particularly through the “journeying” motive, a non-legato, repeated pitch pattern that often appears at the beginning or end of some songs, symbolizing the footsteps of the wanderer.* Youens, Retracing a winter's journey: Schubert's Winterreise.

I was particularly interested in incorporating sonic elements tied to memories of a specific past time, likely situated around the late 1980s/early 1990s. These are evoked through electronic sample sounds –such as telephone ringing tones and cassette players in Oscillations (ii) and Oscillations (iii), and radio-related sounds like dial sweepings and white noise along with certain musical fragments in Oscillations (iii). In addition, the visual narrative proposes an aesthetic strongly related to that particular time, by the use of analog VHS effects and glitches.

Evocations and Connections

One of the creative ideas of these pieces was intended to create musical connections between the oscillating mental states of the wanderer in the original Winterreise and certain sonic and musical material and developments in Oscillations. These connections were intended to evoke the emotional landscape inspired by some of the poems of the cycle, in order to make more vivid the psychological experience of the wanderer. Other connections come from more semantic and referential associations, such as some train sounds and steps as references to movement and displacement.

The use of musical connections to evoke emotions has a long history in Western music,* Particularly relevant is the concept of affects in the Renaissance and Baroque periods and their connection to rhetoric. I will revisit this later to discuss the background of the piece Elevator Pitch. with a vast tradition that has produced many clichés. However, my associations between music and emotions are strongly shaped by my personal, familial, social, and cultural background. In particular, much of my subjectivity is deeply connected to musical traditions from my country, from films, television, music that discovered while growing up, music that I involuntarily listened to, music that I studied at University, and many other sources that are stored in my memory. This inevitably biases my creative. That said, I deliberately attempted to resist the force of cliché by developing more subtle, covert ways of incorporating these connections. This approach could be seen as a heuristic strategy: Do it, but not so obviously.

I’ve come to realize that this is a common practice in WACM. However, the underlying reason for this tendency —to do it, but not so obviously— is less clear. Issues such as expectations, valuations, relevance, stylistic considerations, etc., undoubtedly influence these decisions. Still, I know I would never make these connections overtly. Why? That remains an open question.

In Oscillations (i), my focus was on evoking spectrum of emotions such as despair, love, and contemplation. Clearly, Winterreise addresses a much more nuanced emotional range. However, I chose to distill these states into three broad emotional abstractions* Again, this idea might be seen in connection to the idea of affects, as existed in the Renaissance and Baroque. that, when explored musically, might lead to diverse outcomes. Essentially, the choice of singing style and some of the electronic sounds are aimed at triggering some association between them and these emotions. For example, some historical connotations that the musical material evokes, such as an expressive arioso line, might be strongly associated with love and affection. On the other hand, a low and dark vocal fry might relate to anxiety and despair.

Ultimately, the stubborn alternation between these in mm. 58-65 makes it relatively evident to observe these emotional abstractions in terms of contrast.

In terms of the presence of literal elements from the cycle within the music, I conveyed a certain sense of presence by bringing in reminiscent components, like melodic contours or fragments of poetry. Occasionally, recognizable musical or literary elements emerge dramatically.

At other times, the elements of the cycle gradually emerge from different materials, transitioning until these recognizable elements become distinctive. This approach also employs the “deviation” heuristic, although without utilizing a computational tool, such as NeuralConstraints.

Some other times, the connections between the original Winterreise and Oscillations are structural and abstract, and non directly perceptually relatable. For example, I use melodic profiles, such as from the song “Gute Nacht,” as a break-point functions that later I use to create new melodic profiles, using processes of expansion and contraction.* I will discuss this process deeper in the chapter ‘Joining the Threads’ in particular for the piece I am a Strange Loop.

The three pieces that make up the cycle are designed to be independent and can be performed individually. However, some connections can be traced between them. I often use acoustic pattern-based matching –such as equivalent energy curves of certain gestures– to create aural connections between the pieces. For example, a crescendo sound that originates from a heavily processed sample (the pedal of a piano is struck and allowed to resonate, then inverted) that gradually overtakes the entire texture and culminates in a sudden silence, can be found along the three pieces of the cycle. Usually, this gesture marks the end of a formal section.

The granulation of the same pedal sound sample discussed above resulted in a sound that resembles the march of a train. This sound can be heard along the three pieces as a blueprint that creates a certain sense of dynamism and movement.

Visuals

Finally, the element that connects the three pieces of Oscillations is the visuals. The composition of this layer was in charge of Andrea Urstad Toft. We had several meetings in which we discussed possible connections between the music and the visual narratives. A common point was the use of VHS aesthetics, especially tape glitches. In terms of material, my role was concerned with general suggestions of elements, or pointing at the poetry of Winterreise as a source of imagery.

The first piece, Oscillations (i) is time-locked to the visuals, requiring the singer to follow a click track to synchronize the music with the video. Oscillations (ii) is not time-locked; we defined formal sections and selected specific video material for each. The choice of effects and processes was entrusted to Andrea, with the premise of maintaining a strong connection to the aesthetic we sought. In Oscillations (iii), we incorporated live filming and projection of the performers, following the idea of the doppelgänger in “Der Leiermann” as a projection of the narrator. This concept was extended to the other performers, who are also projected live while playing.